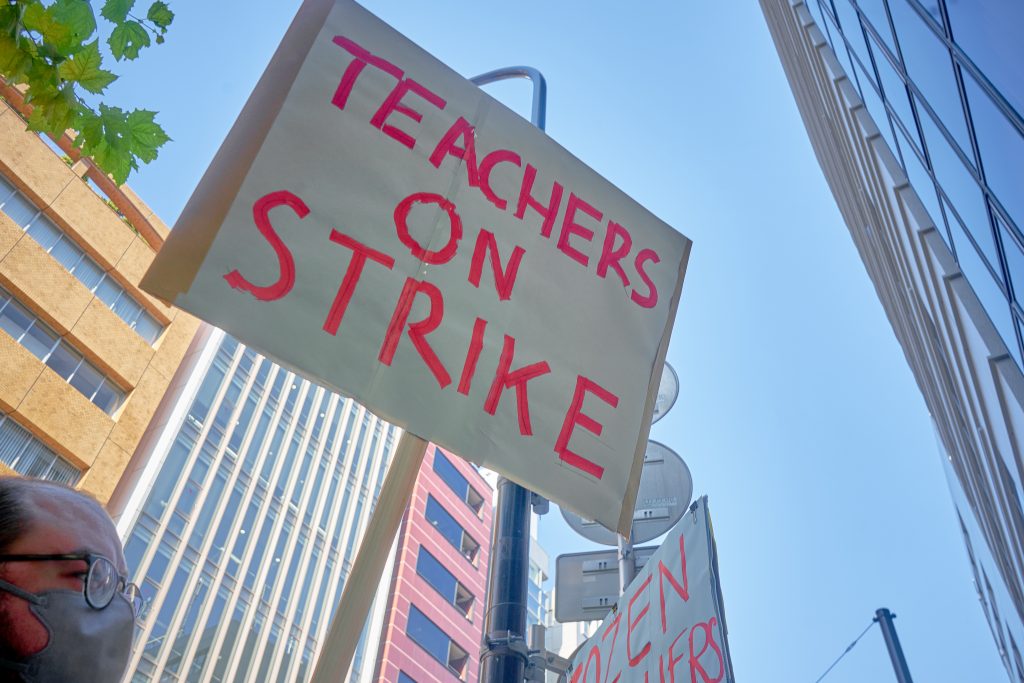

Tozen’s historic Ichinichi Kodo All-Day Action fights for job security, higher wages; breaks through factionalism

Dec. 21, 2021. Under the crisp blue skies of Winter Solstice, Tozen Union held its first ever Ichinichi Kodo All-Day Action.

Teachers at three local chapters of Tozen Union raised their fists and voices in front of each employer, demanding job security, Shakai Hoken health and pension, and a living wage.

In addition to Tozen’s long-allied independent unions, all three national labor federations (Rengo, Zenroren, and Zenrokyo) joined the action, warming our hearts on this first day of winter.

Rengo Tokyo provided the sound car for the day.

Joining Tozen for the fight were: Japan Labour Soviet (Rohyo), General Support Union (GSU, affiliated with NPO Posse), Shutoken Union of University Part-Time Lecturers in Tokyo Area and the National Union of General Workers Tokyo Tobu (Tobu Roso).

This day in Tozen history represented a pushback against the chronic factionalism of Japan’s labor movement. The faction-transcending unity made us forget the cold and gave management a peek at the kind of solidarity arrayed against them.

More than 50 Tozen and allied members squeezed into a tight, thin line on a sliver of sidewalk in front of the Shane HQ office. In a large voice, we demanded the English conversation school give us job security and Shakai Hoken.

Our displeasure at relentless management attacks against workers and the union during this protracted labor dispute burst forth over the speakers of our sound truck. A contingent of Shane members went into the HQ office to submit a written appeal. A manager took it, then flippantly remarked ‘Merry Christmas.’ Our Shane local won’t rest until they win stable working conditions.

The throng walked a block away to Kanda University of Foreign Studies (KUIS). We demanded the school remove its unilateral and arbitrary 6-year limit on employment and agree to open-ended employment for teachers. These educating every day show pride and passion in inspiring the minds of their students.

These teachers want to continue to teach beyond the six years, but the university administration asserts that after six years they are no longer capable of creating anything new. Kaiten (rotation) is necessary to keep the education development fresh, management insists. Members angrily shouted that “KUIS teachers are not dried out conveyor belt sushi!”

The crowd traveled by subway to Ginza, to the headquarters of ALT-dispatcher Interac. We protested the company’s refusal to provide a living way or enroll ALTs in Shakai Hoken. A contingent separated, entered the high-rise office building, and rode the lift to Interac headquarters. There, they tried to hand over a written appeal. Management made them wait for over 20 minutes. The delegation decided to send it later by post; they returned to the lively protest down on street level to give a report to their comrades.

One university student from GSU recounted how an ALT (assistant language teacher) had helped her learn ‘living English.’ She called on the company to recognize a living wage and said that ALTs are not ‘assistants.’

We finished with a sprechchor, bringing life to the soul of workers, who know no faction, under the Ginza winter sky in the middle of the big city

The labor unions and individuals who joined us in solidarity made this historic day possible.