「私はいま、東京に本社がある○○というコンサルティング会社で働いていて、もうすぐ3年になります。実は昨日、突然人事部から全社員にメールが来て、『〇〇社の従業員代表について信任投票を行います。従業員代表は、就業規則変更などの際に、従業員を代表して会社に意見を伝えていただくことになります。このたび〇〇社の従業員代表として、△△さんが推薦され、ご本人からもその候補者になる旨の申し出をいただきました。

law

A democratically elected rep is every worker’s legal right

Last week Mr. A came to me for a labor consultation.

“I have worked for Company A for nearly three years,” he said, “and recently I received an email from human resources announcing an election for workers’ rep (jūgyōin daihyō). The email said that the rep’s job would be to communicate the opinion of the workforce on any changes to work rules (shūgyō kisoku), and that Ms. B had been nominated for the post. It went on to say that if an objection from a majority of employees was not received by a certain date, then management would consider her the victor.”

It was the first time Mr. A had heard anything about such a position. He asked me, “What on Earth is a workers’ rep? What do they do? I have nothing against Ms. B, so should I just leave it to her?”

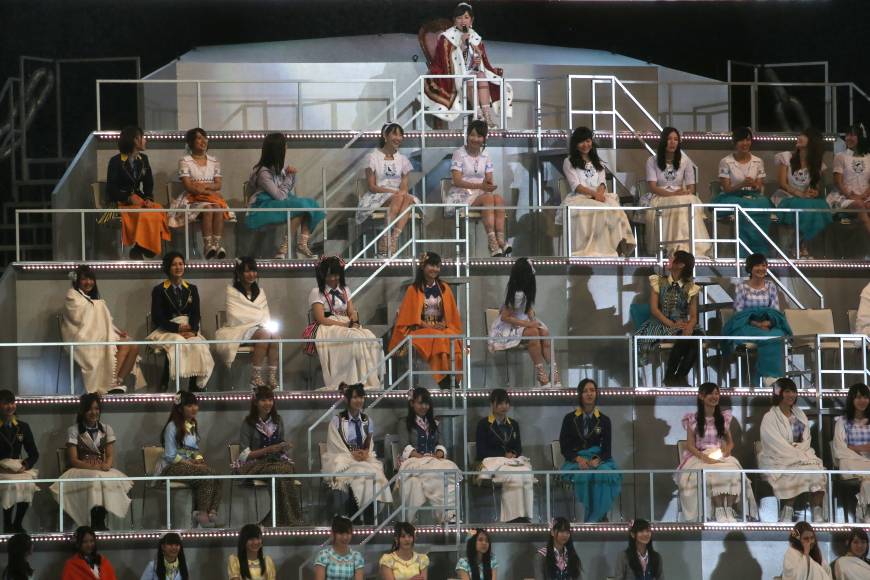

AKB48 members deserve to get workers’ comp for saw attack

On May 25, a man wielding a saw attacked and wounded 19-year-old Rina Kawaei and 18-year-old Anna Iriyama, two members of bumper girl group AKB48, and a male staffer at an event where fans get to shake hands with their AKB idols.

Fortunately the injuries were minor, but fans were shocked. The victims and their AKB48 comrades must have been terrified.

Japan moves to expand controversial foreign worker scheme

(Reuters) – Japan is considering expanding a controversial program that now offers workers from China and elsewhere permits to work for up to three years, as the world’s fastest-aging nation scrambles to plug gaps in a rapidly shrinking workforce.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party on Tuesday submitted a proposal to let workers to stay for up to five years, relax hiring rules for employers and boost the number of jobs open to them.

Tozen VS ICC

Tokyo General Union (Tozen) protests the firing of member Sulejman Brkic in front of the language school ICC. He worked there for 22 years and was fired for asking for his legally allotted paid holidays.

Trailer:

Full Version:

Restore the shuttered-up New Year’s of yore

BY HIFUMI OKUNUKI

First of all, I would like to wish a happy new year to all the readers of Labor Pains. While labor news has generally been a gloomy topic of late, it is my hope that this year will bring brighter things for me to write about.

As I draft this first column of 2014, I am sitting in front of my computer at 10 at night in my apartment in downtown Tokyo. The suddenly vacated metropolis is blanketed in an uncanny hush. Hardly any cars can be seen passing by. In the great New Year’s exodus, many of the inhabitants of Tokyo have returned to their various hometowns across Japan, leaving the city in a temporary state of near-abandonment.

I can’t say that I’ve ever disliked this vacated Tokyo. In fact, I enjoy the calm atmosphere. Watching “Kohaku” (an annual pop music contest televised on New Year’s Eve), chatting about this and that, eatingtoshikoshi soba (a noodle dish with tempura served on Dec. 31) — this kind of traditional New Year’s Eve suits me just fine. And, even if I were to absentmindedly forget the tempura for the soba, I wouldn’t have to worry because, in this day and age, most supermarkets remain open all through the holiday season. It is no longer rare to see a supermarket open its doors even on New Year’s Day.

It wasn’t always like this. Back in my day, we took it for granted that for the period from the evening of Dec. 31 to Jan. 3, nearly everything would be shuttered up. On the morning of New Year’s Eve, stores would be scenes of chaos, packed with shoppers frantically stocking up on supplies to last the week. My mother used to take my sister and me along as well, to help carry bags for her, and both of us would barely be able to hold all the shopping. For us kids, the pressure of knowing that if we forgot something we would have to do without it over the holidays brought with it a strange sense of excitement.

But today’s young people have probably never experienced all that. Convenience stores that open 365 days a year, 24 hours a day now dot the Japanese landscape, and supermarkets are closely following with ever longer business hours, to the point that the end of the year no longer feels like such a special time.

I sometimes wonder if this new “convenience culture” is a good thing. Of course, from the standpoint of consumers, being able to buy anything you need any time provides a sense of security, and this convenience could be considered to be something positive. But at the same time, if we look at it from the workers’ perspective, that convenience comes at the direct cost of more labor through the holiday period. Convenience stores, supermarkets, DVD rental shops, family and fast food restaurants,izakaya, karaoke parlors — all kinds of establishments remain garishly and noisily open for business in spite of the New Year’s holiday.

The people working at these places have to sacrifice their private lives for the sake of their jobs. Of course, you could argue that the people working at these stores freely choose to do so. However, I doubt that most of the people working in these jobs are in a position to make very “free” choices. Rather, I suspect that they are cajoled or even coerced into taking these shifts. I can’t help but have misgivings about the idea of forcing people into situations where they have to make personal sacrifices for the sake of customer convenience.

For contrast, let’s look at how the same issue is handled in another country. In Germany in 1900, a law called the Shop Closing Act (Ladenschlussgesetz) was passed that remains in force to this day. Under this law, shops are in principle not allowed to open outside the hours of 6 a.m.-8 p.m. on Mondays to Saturdays — or at all on Sundays and national holidays. While airports and train stations are exempt and many other revisions have followed over the years, gradually resulting in the law being relaxed significantly, the Shop Closing Law continues to regulate business hours in Germany.

The motivations behind this act were threefold. First, for religious reasons, the government wanted to preserve Sunday as the Christian Sabbath. Second, the law’s proponents hoped to protect the livelihoods of “all workers.” They feared that longer business hours would result in employees being forced to work longer hours to match. Third, the government wanted to protect small businesses. In other words, it worried that with unregulated business hours, large companies that could afford to extend business hours would gradually rob smaller companies of their customers and thereby threaten their very existence.

As I’ve written about over and over in my Labor Pains articles, overwork is one of the most serious social ills afflicting Japan today. About 5 million people — 10 percent of Japan’s workforce — toil more than 60 hours a week, according to a 2012 study by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

Theoretically, Article 32 of the Labor Standards Law gives workers the protection of the eight-hour day and the 40-hour week, and bans work above those limits. However, exceptions to this law are often recognized. While so-called 36 Agreements (a kind of deal struck between workers and management about overtime, named after Article 36 of the same law) are required for overtime to be permitted, in practice many companies are able to extract unpaid overtime from their workers without concluding any such deal.

On top of that, in an investigation published on Dec. 30, the Tokyo Shimbun found 1,343 cases of companies that incorporated “fixed overtime pay” lump sums into regular wages and then forced workers to work past the hours originally set in their contracts or, alternatively, did not even give a clear figure on how much overtime was being paid for.

Furthermore, under the Labor Standards Act, provisions exist allowing for flexible arrangements such as irregular working hours, flex-time, work outside the workplace and discretionary labor. (Under the discretionary labor system, employer and employee are supposed to decide between them how long a job should take, with the employer then paying the worker for those hours regardless of how many hours are actually worked.) In other words, the law that is supposed to protect the health and livelihood of workers in Japan is riddled with loopholes, and the country is sadly filled with employers willing to exploit these loopholes and overwork their employees.

So once again this year, I have ended up returning to a gloomy theme. However, this New Year’s Day, I dare to dream of how different things might be if we were to look at the people working at our convenience stores, supermarkets and restaurants not from the perspective of consumers blindly seeking convenience, but, like the framers of Germany’s Shop Closing Act, as people who believe that all workers should be protected.

In that spirit, and not out of nostalgia, I suggest that we work to bring back the old, shuttered-up New Year’s Day.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union (Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union). She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. On the second Thursday of each month, Hifumi looks at cases in Japan’s legal history to illustrate important principles in labor law.

Originally published here:

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2014/01/08/general/restore-the-shuttered-up-new-years-of-yore/#.UtdzeHnCWwe

The year in labor: the Top 5 pains of 2013

By Hifumi Okunuki

Illustrations by Time O’Bree

Japan’s old calendar called December shiwasu (師走). These two kanji mean “teacher” and “run.” The idea was that the last month of the year is so busy that even a staid, starch-shirted professor finds him or herself scurrying around like a rabbit, trying to get everything done on time.

As we hurtle toward 2014, it’s time to look back on how the Year of the Snake treated labor. In keeping with the growing trend on TV, blogs and news sites, I’ve devoted this final edition of the year to a Top 5 list. The Top 5 Labor Pains of 2013 will focus on what really shook things up in terms of labor relations and employment law. In keeping with convention, I’ll count backwards.

Note: These are my personal picks and you may question my choices or believe other labor news to be more deserving of inclusion. If so, please don’t hesitate to let me know.

5. The planned ‘special dismissal zone’

The media jumped on the plan, calling the proposed area a “dismissal zone,” to which academic Tatsuo Hatta, the head of the working group, retorted, “It’s a job creation zone, not a dismissal zone.”

What kind of jobs do these planners intend to create for us? Since firms are free to employ and un-employ workers at will, these workers will in effect become interchangeable parts in the corporate machine. For every job created, employers can cherry-pick which workers to let go, leading to massive turnover and great social instability.

The plan raised such an uproar that it has been put off for now. But proponents will not roll over so easily. When the winds are right, they are sure to give it another shot.

4. Rin Danda, labor standards inspector

I cannot overemphasize the significance of the fact that a labor standards inspector was made the protagonist of a TV series.

I had already read the comic book “Dandarin,” which follows the adventures of plucky Rin Danda, and was concerned that something might be lost in translation en route to TV. I have been reassured by the first series, which ended Wednesday. It is obvious that producers have researched the Labor Standards Bureau properly and have carefully avoided making the script preachy.

Ratings have been poor, but the series has gone a long way toward conveying the reality facing the modern worker in Japan.

3. The Fukushima far-more-than-50

Do you remember the “Fukushima 50″? They were the workers who struggled frantically to regain control over the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant just after the triple meltdown caused by the March 11, 2011, Great East Japan Earthquake and ensuing tsunami. The domestic and foreign media heaped accolades upon them, suggesting they were heroes burning with a sense of mission who demonstrated remarkable courage in fulfilling their duties with scant regard for their own lives.

More than 2½ years have passed, yet the government and society have nearly forgotten those who still toil day and night at the plant. If they were to drop their tools for even a night, the resulting contamination could leave our country uninhabitable. And it isn’t just 50 of them anymore — let’s recognize the thousands of heroes who have worked, still work and will work at the Fukushima No. 1 plant to contain the contamination and protect our environment.

And what are working conditions like for these heroes? Unfortunately, many workers there are slaving under horrible sweatshop conditions. Tokyo Electric Power Co. hires layer upon layer of subcontractors, sub-subcontractors and so on, with most workers involved in the cleanup eking out a living on the very lowest tiers of this exploitation pyramid.

The biggest problem with this structure is that no one can figure out who is accountable for employment and working conditions. With little or no preparation or training, these workers are suddenly thrust into highly dangerous tasks beyond the reach of labor law but well within the reach of harmful daily doses of ionizing radiation. Even their “danger pay” is skimmed by their bosses and their bosses’ bosses.

Most workers grin and bear it without a peep of protest, fearful of losing the only job they can find. Recently, however, one worker employed by a fifth-tier subcontractor took action. He was told upon hiring that he would not have to work in dangerous conditions, yet he was assigned to increasingly high-exposure tasks, such as removing glass near one of the reactor buildings. The day after he protested that he had been promised a safe job, he was fired.

He joined a labor union, which requested collective bargaining with five companies, including Tepco itself, over demands such as reinstatement, an end to false outsourcing (gisō ukeoi) and the payment of the promised danger money. Only his direct employer — the fifth-tier subcontractor — agreed to negotiate. His union sued Tepco and the other defiant firms in the Tokyo Labor Commission for refusing to engage in collective bargaining. Tepco claimed to know nothing of the request for collective bargaining and refused to comment.

Going on three years since the accident, we still have little to show in terms of protecting the rights of nuclear power plant workers.

2. ‘Black company’ makes it into Top 10 buzzwords

The winning “Buzzwords of the Year” for 2013 in the annual contest held by publishing house Jiyukokuminsha and correspondence education provider U-Can were “Ima desho!” (Why not now!), omotenashi (hospitality),jejeje (an expression of surprise) andbaikaeshi (double payback). I won’t go into the above expressions here, but I will discuss burakku kigyō, which made the Top 10.

Literally, the term means “black company,” but it might more properly be rendered as “evil corporation.” The phrase describes firms who find profit and success by scoffing at labor laws and brutally exploiting employees, particularly young workers who do not know the law. Some companies literally work their employees to death. Or suicide.

The word went viral thanks to the efforts of Haruki Konno, the director of the labor consultancy NPO Hojin Posse.

Some have pointed out that using a term derived from the English word “black” to mean “evil” is racist toward those of African descent. There are many words in Japanese that seem to associate “black” with negative things:kuroboshi (defeat), haraguroi hito (mean person) and kuro (guilty), to name but a few. There are also exceptions: kurooto (professional) andkuroji (profitable), for example.

For better or worse, burakku kigyō has seeped deep into the language this year and has raised awareness of the existence of some very bad companies. While this is certainly a social problem, it’s also true that it’s up to workers to stand up for themselves and join forces with their colleagues to improve their conditions.

1. Clock starts on the ‘five-year rule’

I had difficulty deciding which Labor Pain to pick for the No. 1 spot this year. In the end, I decided that the “five-year rule” may end up having the greatest impact on workers — for good or ill, it remains unclear. For my part, I cannot help being pessimistic about this change to the Labor Contract Law.

About 26 percent of workers in Japan are on fixed-term contracts. The risk of nonrenewal hangs over their heads each time their contract concludes. It is much easier to fire such workers than those with ordinary permanent contracts. Many companies hire workers on these temporary contracts even though the work is anything but. This “permatemp” status continues year after year and renewal after renewal.

The purported objective of the new rule is to increase job security for the millions on such contracts by letting them attain permanent status after five years. Many employers, however, have decided to go 180 degrees against the spirit of the law and are already planning to let workers go before they reach the five-year milestone, thus making their jobs even less secure.

A small minority of employers are bucking this trend and moving actively to let their workers attain permanent employment status. But even this year — the first year of the five-year “clock” — we see want-ads flooding job sites advertising positions with five-year ceilings.

More frightening still, while employers seem to know enough about the law to evade it, a September study by Japan’s largest union federation, Rengo, indicated that 88 percent of workers on fixed-term contracts were unaware of the nature of the change to the Labor Contract Law. That has to change. We need to know the law in order to use it.

I want to thank all my readers for taking the time to read this year’s 12 Labor Pains. Next year, I plan to take the column in an all-new, more fun direction. Have a good New Year’s and see you in the Year of the Horse.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union (Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union). She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. On the second Thursday of each month, Hifumi looks at cases in Japan’s legal history to illustrate important principles in labor law. Send your comments and story ideas to community@japantimes.co.jp.

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2013/12/11/general/the-year-in-labor-the-top-5-pains-of-2013/