Eikaiwa

GABA Dispute Update

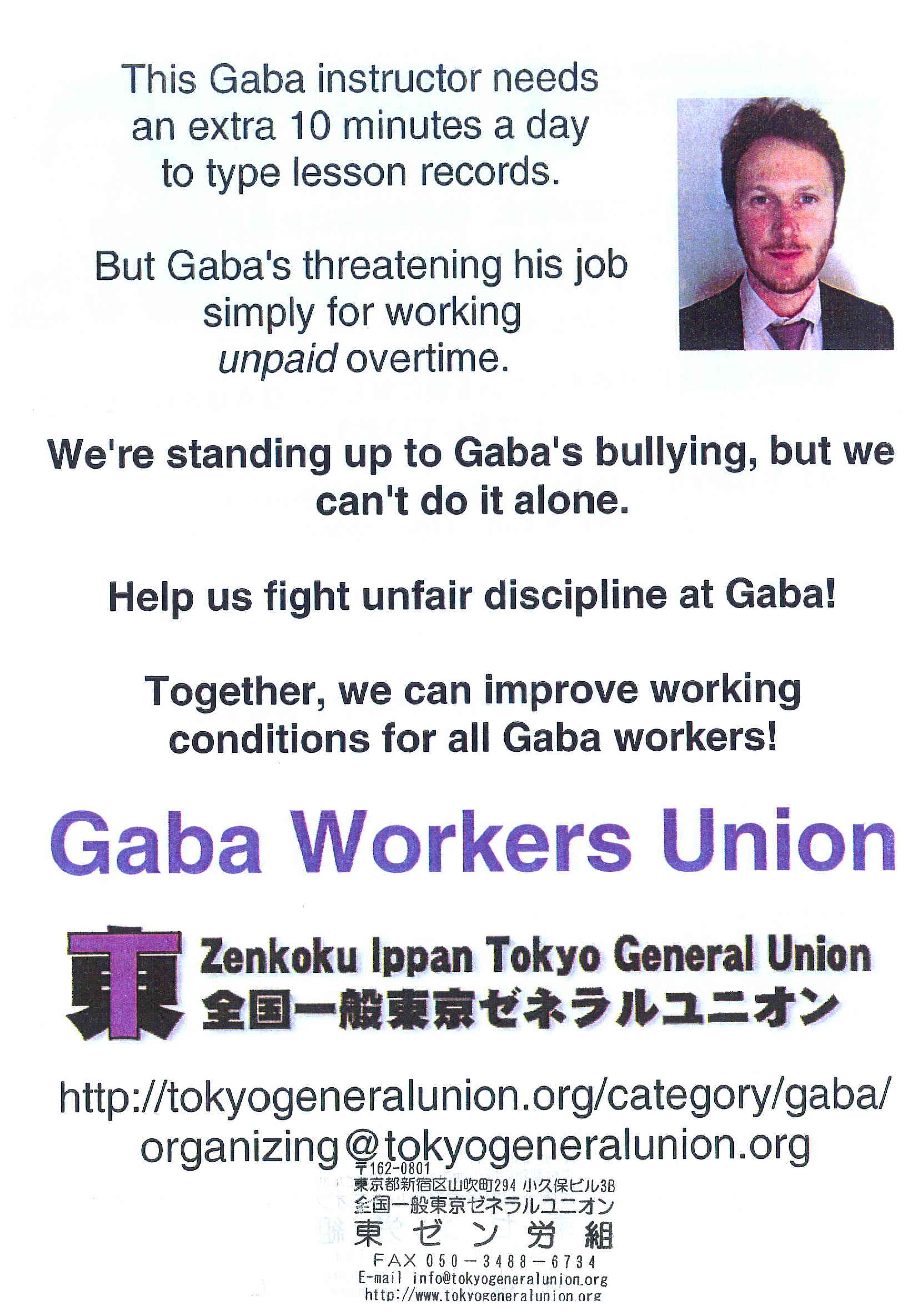

The Tozen GABA Local leafleted the GABA Tokyo Learning Studio this morning in protest of their unfair discipline towards local president Tyler Christensen. The GABA Local also leafleted the Yokohama LS on Saturday night. On each occassion the union leafleted to both clients and instructors there – to let them know about Gaba’s persecution of Tyler. The responses were really positive; people continue to be outraged by Gaba’s seemingly senseless refusal to negotiate. Afterwards, the Local held its monthly meeting at a nearby restaurant, which prospective members could also attend. Tozen’s Gaba local continues to grow.

Tozen Report: All Day Dispute Action Against GABA

Last Friday, Tozen GABA Workers Union took its first all day action against GABA’s threat to fire Tozen GABA Workers Union President Tyler Christensen.

We began at 6AM to leaflet GABA Shinagawa Learning Studio. We moved on to Gaba corporate HQ at 9AM. There as we handed out leaflets, GABA representative Satomi Odaka emerged from the building.

The union handed Mr. Odaka a notification of dispute, outlining the specific demands of our dispute. You can read about them here. Mr. Odaka responded by asking for our “road use permit,” which we don’t need, physically obstructing Case Officer Gerome Rothman and threatening to call the police.

GABA then took the step of calling the police in an attempt to shut down our protest. We explained to the police that we were conducting legitimate union activity. The police decided not to interfere.

We did a loud protest call with the megaphone, and concluded our action. After that, we filed a protest with the company demanding an apology for their obstruction of legitimate union activity. We demanded they follow the law and desist from interference with union activity.

Tozen went to Yokohama Learning Studio, where Tyler works. During leafleting, Tyler spoke directly to his colleagues, sharing his story and drawing their support. He also took to the megaphone in an appeal to GABA management, asking them to “Let me do my job.”

GABA members and Tozen supporters wrapped up their protest at the end of the GABA work day, in Chiba. We leafleted at the Chiba Learning Studio.

Our first protest against GABA spanned 2 prefectures and the Tokyo Metropolis, 3 Learning Studios, and GABA HQ. We confronted a hostile management, and meaningfully engaged with sympathetic members of the GABA community.

We would love to think that a marathon fourteen hours of protesting GABA’s stubbornness will mean the end of our struggle for Tyler. We know, however, this is just the very beginning.

We need your help.

Tozen will not back down when its members are threatened with unfair discipline and attacks on their rights as workers. Tozen knows that all workers in Japan have the right to join a union, negotiate with management, and take collective action to improve their working conditions.

Join our fight. Let’s make GABA better for everybody.

Tozen Gaba Workers Union in Dispute with Gaba 全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオンGABA労働組合はGABAに対して労働紛争

The Tozen GABA Workers Union is officially in dispute with the company over it’s unfair disciplinary action (不当懲戒処分) against Local Executive President Tyler Christensen.

We are fighting for the right to work unpaid overtime.

Say what?

Yes, we are fighting for the right to work unpaid overtime without facing discipline from the company.

Tozen VS ICC

Tokyo General Union (Tozen) protests the firing of member Sulejman Brkic in front of the language school ICC. He worked there for 22 years and was fired for asking for his legally allotted paid holidays.

Trailer:

Full Version:

Teachers tread water in eikaiwa limbo

BY CRAIG CURRIE-ROBSON

Jan 22nd, 2014

Every year, thousands of young native English-speakers fly to Asia in search of an adventure, financed by working as English teachers. They come from Australia, New Zealand, the U.S., Britain, Canada and elsewhere.

But it can be risky leaping into another country on the promise of an “easy” job. In Japan’s competitive English teaching market, foreign language instructors are treading water. “Subcontractor” teachers at corporate giant Gaba fight in the courts to be recognized as employees. Berlitz instructors become embroiled in a four-year industrial dispute, complete with strikes and legal action. Known locally as eikaiwa, “conversation schools” across the country have slashed benefits and reduced wages, forcing teachers to work longer hours, split-shifts and multiple jobs just to make ends meet.

The British Council: friend or foe?

http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2012/oct/08/british-council-education-training

Educators working overseas complain that the venerable quango’s business interests have turned it into a rival

Jonn Elledge

The Guardian,

A few years ago, when the CfBT Education Trust, a non-profit organisation that runs schools and education services, was looking to expand its operations in Malaysia, its chief executive, Neil McIntosh, arranged a meeting with the local high commissioner. When he got there, though, he was disappointed to see that the commissioner had brought along a representative of one of CfBT’s main competitors. “He was a bit put out that I should see the British Council in that light,” says McIntosh.

The British Council, it’s widely thought, is a thoroughly good thing. It is the epitome of soft power, a long-established arm of the Foreign Office that promotes British interests not with bombs and guns, but through culture and education. A big part of its job is to promote UK education: by marketing domestic universities to international students, or providing local intelligence to any education provider that wants to work overseas. Officials often suggest the council’s local office should be first port of call for any company looking to enter a new market.

Consequently, McIntosh admits, criticising it feels a little bit like “crying foul on someone’s much-loved grandmother”. But the British Council isn’t just a charity. It is also an increasingly ambitious player in the global market for English languageteaching, exam provision and other education services. It holds a one-third share in the International English Language Testing System, for example, and takes on contracts to train teachers for overseas governments.

Now questions are being asked about whether such activities conflict with the council’s role in supporting other providers, like CfBT. Says McIntosh: “It makes it more difficult for us to compete with America and Australia, whose diplomatic missions represent their education systems more comprehensively.”

McIntosh is not alone in his views. “Every company I know has concerns about the British Council,” says Patrick Watson, managing director of Montrose Public Affairs, which works with a number of firms. “It uses its monopoly position aggressively: if you don’t play ball, it can simply ignore you or decide to collaborate with someone else.”

One business leader even says: “The British Council doesn’t really enable British education exports: it inhibits them.”

The council itself rejects such criticism robustly. Dr Jo Beall, its director of education, points to all the work it does to promote British education: enabling academic partnerships with India and Brazil; telling the world that UK universities are open for business. “It’s because the British Council has been flying the UK flag for nearly 80 years that there’s such a strong market in the first place,” she says.

The root of the row lies in the council’s unusual funding model. It is a quango, sponsored by the Foreign Office, that exists to promote British education and culture. That, in ministers’ minds, includes supporting private education firms seeking export opportunities.

But as its grant has been cut, the organisation has had to shore up its finances by selling its own education services: English language teaching, teacher training, and providing exams. Overseas governments seeking a bit of British educational expertise often appeal to the British Council for help. In some cases, it steps in to provide that help itself, and rivals complain there are no clear criteria explaining which contracts it will pass to the industry and which it will hang on to. “Human nature being what it is,” says Andrew Fitzmaurice, chief executive of international schools firm Nord Anglia, “I suspect they’re always going to keep the best ones.”

The upshot of all this is that the British Council sometimes promotes others and sometimes promotes itself. Many companies are wary of asking for its support, either because they are reluctant to share information with a competitor, or because they think the council would be unwilling to help. “I never gave the British Council a moment’s consideration as a source of information and support,” says Kevin McNeany, chair of Orbital Education, who has worked in the sector for more than 40 years. “Even if they had information of commercial value, it would first be filtered through its own internal networks to see if it could be monetised for in-house benefit.”

The critics have other complaints, too. The British Council’s not-for-profit status means it is exempt from corporation tax in many countries, so in some cases can undercut competitors. And in some regions it also works closely with the British embassy. “I am never going to get a meeting with the ambassador at short notice,” says one angry executive. “For the British Council, it’s just a short walk along the corridor.”

Actually, British Council spokespeople point out, it co-locates with the Foreign Office in fewer than a quarter of the countries where it works, and it does so only for reasons of security or cost. And they say there are protocols in place to stop the council’s commercial and charitable arms from sharing information. Its tax advantages, they point out, merely reflect the fact that it doesn’t make a profit, but uses all income to support its work promoting Britain abroad. Its chief executive, Martin Davidson, is very proud of all this, describing the set-up as “a model of entrepreneurial public service”.

Another complaint, though, is that the council’s commercial goals could affect its advice. Its Education UK website is intended to be the front first port of call for international students looking to study in the UK. But the most visible listings are those schools and colleges that have paid for the privilege: potential students are less likely to discover the course best for them, more likely to see the one with the biggest marketing budget. “Institutions are welcome to pay for extra promotional services,” Beall admits. But she rejects any suggestion that this means the site is biased towards certain institutions, and points out that the council makes no money from the website.

“The problem is not created by the British Council itself,” says McIntosh. “It’s created by the government, which requires the council to fund itself by competing with the organisations that it’s supposed to represent. That is not a sustainable position.”

Beall, though, rejects this entirely. “I really resent that idea that we should move out of this [commercial] space,” she says. “It’s tantamount to a private university saying that all public universities should vacate the market.”

The government does not seem convinced of the case for reform. In 2010, a group of education bosses led by McIntosh wrote to Francis Maude, cabinet secretary, about the British Council’s operations (as well as other quangos), requesting he take action. Maude promised no remedy. A delegation that met the trade minister Lord Green over the summer report a distinct lack of concern. Whatever the gripes of education businesses, the British Council is here to stay.

Berlitz court ruling unequivocal on basic right to strike

Language school firm will appeal decision

After hearing more than three years of testimony, the judge took only a minute to read the court’s verdict rejecting Berlitz Japan’s ¥110 million lawsuit against striking teachers and their union and reaffirming organized labor’s right to take industrial action.

According to the Feb. 27 Tokyo District Court ruling, “There is no reason to deny the legitimacy of the strike in its entirety and the details of its parts — the objective, the procedures, and the form of the strike. Therefore there can be no compensation claim against the defendant, either the union or the individuals. And therefore it is the judgement of this court that all claims are rejected.”

The battle of Berlitz began on Dec. 13, 2007, when teachers belonging to the Berlitz General Union Tokyo (Begunto) launched a strike against Berlitz Japan. The teachers, who had gone without an across-the-board raise for 16 years, struck for a 4.6 percent pay hike, a one-off one-month bonus and enrolment in Japan’s health insurance and pension system.

The strike grew into the largest sustained industrial action in the history of Japan’s language school industry. Over 11 months, teachers of English, Spanish and French struck 3,455 lessons in walkouts across Kanto.

In November 2008, Begunto filed an unfair labor practices suit at the Tokyo Labor Commission. The union alleges Berlitz Japan bargained in bad faith and illegally interfered with the strike by sending a letter to teachers telling them to stop walking out.

On Dec. 3, 2008, Berlitz Japan, claiming the strike to be illegal, sued for ¥110 million in damages. Named in the suit were the five teachers volunteering as Begunto executives, as well as two union officials: the president of the National Union of General Workers Tokyo Nambu, Yujiro Hiraga, and Louis Carlet, former NUGW case officer for Begunto and currently executive president of Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union (Tozen).

Berlitz Japan claimed the union’s tactics of giving strike notice at the last minute and making it difficult for the company to bring in replacement teachers were illegal and designed to harm the company.

Begunto filed additional complaints against the company at the Tokyo Labor Commission in 2010 after Berlitz Japan dismissed two of the union executives named in the lawsuit. One teacher lost his job after he requested a leave of absence of more than a year in order to serve as a reservist in Afghanistan, the other after she requested an additional four months unpaid leave to recover from late-stage breast cancer.

Yumiko Akutsu, one of the union’s lawyers, told supporters after the verdict that the win was “a complete victory — on not one point did we lose, not one single point.”

Reading from the court’s ruling, she explained that the court found the objective of the strike to be legitimate because “the strike’s purpose was to realize the union demands they had clearly stated to management in 2007 and 2008.”

Because teachers had different work schedules at different language centers and often didn’t receive their schedules until 7 p.m. the night before working, the court also rejected the company’s claims that the last-minute notice given by teachers before striking lessons was illegal. “Strike notice just before the strike cannot be considered illegitimate”, the court ruled.

After the win, Carlet stressed the significance of the victory as an important defense of the right to take industrial action in Japan. “This is a very important victory for the right to strike,” he told union members. “I think people often forget how important the right to strike is. The right to strike was not granted us by governments or by management. Workers fought in many countries around the world and gave their blood, sweat and tears to win this right to strike.”

Hiraga also emphasized the significance of the win, telling union members, “I think what the verdict represents is that the company sued you for damages as a way to weaken the union and as an illegal union-busting tactic, and it was denied by the courts.” Calling it a triumph not only for Begunto and Nambu, Hiraga told supporters, “This is a victory for the entire labor movement in Japan.”

According to Akutsu, a victory by the company “would have had a huge impact and a huge chilling effect on people’s willingness to strike.”

Gerald McAlinn, a professor at Keio University Law School, said that because Article 28 of the Constitution guarantees the right of workers to organize and bargain collectively, “Any decision by the court to the contrary would have been very strange and contrary to the fundamental rights of all workers in Japan.”

McAlinn emphasized three reasons for the importance of the case. First, “A ruling in favor of the company would have opened up an avenue for employers to circumvent the balance of power established by the labor union law.” He added that allowing employers to sue striking workers “would be a powerful weapon that could easily be used to chill the exercise of constitutional rights by workers all across Japan.”

The court’s ruling is also significant because of the somewhat unusual nature of the strike action. Unlike in a typical strike, where workers walk out en masse and stay out together, Berlitz instructors sometimes taught and sometimes downed chalk. Individual Begunto members struck individual classes in different language centers at different times, handing their strike notices over to management only a few minutes before the scheduled start of the lesson. This minimized the company’s ability to bring in replacement teachers and break the strike. According to McAlinn, “This case seems to legitimize the practice of refusing to work other than via the traditional all-out-together picket line strike.”

Finally, McAlinn believes the verdict matters because it was mostly foreign teachers in the dock. “The nationality of the defendants should not matter of course, but this decision makes this point clear,” he said.

The triumphant union executive members stress the need to move past legal confrontations and get back to negotiations with management. Hector Coke, Begunto president at the time of the strike and one of the teachers named in the lawsuit, told union members and supporters in a meeting after the verdict that it’s time to start negotiating and “build a better relationship with management. We should not be arrogant in the fact we won this case.”

Paul Kennedy, current Begunto president, echoed this point at a press conference after the verdict. “We look from this point forward to be able to negotiate with Berlitz Japan,” he told reporters. “This is a new start for both sides.”

However, Berlitz Japan didn’t wait long before deciding to continue the legal skirmish. Kennedy says he received notice that Berlitz Japan will appeal the verdict on Friday.

Michael Mullen, Berlitz Japan’s senior human resources manager, declined to comment on the case.

Berlitz Japan doesn’t necessarily have to submit new evidence in their appeal to the high court. “In my experience, the high court is not shy about reaching a decision different from that at the district court level if the judges see the facts or law differently,” said McAlinn. “Having said that, I would be surprised if the high court were to reach a different decision in this case.”

Meanwhile, Begunto and Berlitz Japan continue their legal battle at the Tokyo Labor Commission, buoyed by the district court victory.

“With this verdict,” says Carlet, “we will be in a very good position at the labor commission because the strikes were legal and that will make all the difference.”

However, legal experts don’t all share Carlet’s confidence. According to McAlinn, the verdict “shouldn’t have a direct impact on the union claims at the Tokyo Labor Commission” because “the two actions are governed by different laws and legal standards.”

Tadashi Hanami, former chair of the Central Labor Relations Commission and professor emeritus at Sophia University, agrees, explaining that the Tokyo Labor Commission “may take this verdict in consideration if it chooses so, but we can hardly predict whether it will do so or not because it’s not unusual that courts and commissions take completely different opinions.”

Union members also now face a large legal bill. “The general principle under Japanese law is for each side to pay their own court costs,” says McAlinn. Union members are now discussing ways to recover court costs from Berlitz Japan, says Kennedy.