By Hifumi Okunuki

Last month, a new ANA commercial hit the airwaves — and quickly ran into some serious turbulence.

The scene is Haneda Airport. Two Japanese men dressed as pilots stand with their backs to the camera.

“Haneda has more international flights nowadays,” says one.

“Finally,” replies the other.

“Next stop, Vancouver,” the first man says.

“Next stop, Hanoi,” his friend replies.

“Exciting, isn’t it?”

“You want a hug?” the taller man says, out of nowhere. The shorter man stares at him in bewilderment.

The man who proposed hugging criticizes him, saying, “Such a Japanese reaction.”

“Because I am Japanese,” the man says in his defense.

“I see,” says his partner, before falling into a contemplative silence. “Let’s change the image of Japanese people.”

When the camera returns to the shorter man, he is wearing a blond wig and a false nose of Pinocchio proportions. “Sure,” he says.

A voiceover then intones the All Nippon Airways slogan, “From Haneda to the world, ANA,” and the commercial ends.

As soon as this ad aired, ANA was inundated with criticism. The thrust of the complaints was that the ad was racist and exaggerated the physical features of white people to point of mocking them.

ANA did not seem to have anticipated such a reaction. It swiftly apologized and removed the offending final image from the clip on TV and online. (Though it was only the TV commercial that received criticism, they also took down posters of one of the actors from the commercial wearing the traditional dress of various countries.)

What interested me in particular was the difference between the reactions of Japanese and foreigners who saw this ad. At my labor union there are members of many different nationalities, the large majority of whom expressed unhappiness or indignation toward the ad. “How did they fail to anticipate this would offend people?” many asked.

On the other hand, Japanese people I know reacted with bewilderment. “It’s certainly childish,” their comments tended to run, “but I couldn’t call it racist. On the contrary, since blond hair and big noses are something that in Japanese culture have long been held up as attractive, the ad is more an expression of Japanese people’s sense of inferiority.”

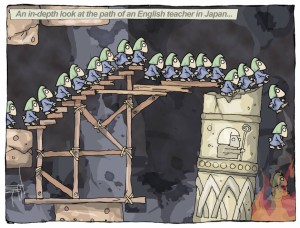

My personal opinion is that the ad is a disappointing anachronism, and a reminder of the parochial outlook of large Japanese corporations. The ad appeals to the facile formula that “foreigner = white = blonde and big-nosed = English-speaking = globalization.” But this feels bizarrely outdated and out of place coming from ANA, a major carrier trying to depict the airport generically — and Haneda in particular — as some sort of stage for exchange between the world’s many races and nationalities. Instead, the ad unintentionally shows that the Japanese archetype of thegaijin (foreigner) remains as strong as ever.

So why is it that so many of the Japanese people I spoke to couldn’t understand why foreigners would be angry about this “racist” ad? I think, fundamentally, it has to do with the very narrow image that postwar Japan has had of what “abroad” and “foreigners” mean. Because postwar Japan has been politically, socially, culturally and in almost every other respect in thrall to the West — and particularly the United States — the view that blond, big-nosed, blue-eyed and English-speaking are somehow “better” or the “global model” is widespread.

At the same time, the former targets of Japanese invasion in Asia, such as China and South Korea, have been largely ignored. Political leaders have avoided the question of responsibility for the war, and ordinary people have relatively little opportunity to study their own recent history. Japan has considered itself as separate from Asia, due to its status as the only Asian country that succeeded in developing into a major economic power. For postwar Japan, “foreign” has basically meant “American.”

As Japan’s own economic engine has puttered out, China has started to grow rapidly and South Korea has become a major hub of popular entertainment and industry, and many Japanese now feel threatened and see these countries as rivals.

The Japanese media have been eager to belittle their neighbors. And so, Japan, which up to now had adopted a “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” attitude to its history of war against its neighbors, is at the stage where its politicians are actively trying to make excuses for its past aggression and are even trying to apportion blame to the Koreans and Chinese.

Japan is thus far from becoming “global” in any real sense of the word. In a nutshell, the world for Japan consists of China and Korea — the objects of resentment and controversy — and the rest, who are all blond, big-nosed English-speakers.

Japanese women’s magazines often run articles with titles like “How to do your makeup for that foreign look” or “half look,” where “foreigner” obviously means “white Westerner” and “half” means “a half-Japanese, half-white mix.” No one who reads these headlines would consider that they could be referring to half-Chinese or half-Filipino Japanese, even though we inhabit a world of around 200 different countries, most of which are majority non-Caucasian.

It’s from this perspective that the trade ministry is raising its voice and calling for Japan to prepare workers with a more “global outlook” and to stop the trend of young people “looking inward” (uchimuki).

This is laughable. It would certainly be better if young people looked out at the world, provided they recognize and appreciate its true ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity — and that this diversity cannot and should not be ranked in terms of which traits are better or worse. That would be some real globalization.

Apologies for the long buildup, but I felt this commercial brought up an important point regarding the situation of foreign workers in Japan. But first, I would like to ask readers what they think: Do Japanese businesses discriminate against foreigners?

Japanese labor law has only one or two articles that touch on the subject of foreigners. The crucial one is Article 3 of the Labor Standards Act, which states that “an employer shall not engage in discriminatory treatment with respect to wages, working hours or other working conditions by reason of the nationality, creed or social status of any worker.”

This is called the principle of equal treatment. Nationality is considered to encompass the concept of race in this article.

It’s not necessarily a bad thing that Article 3 is the only section of the Labor Standards Act that refers to foreigners. Since every article of labor law should apply to every person working in Japan, I don’t think there’s any need to make any special mention of foreigners elsewhere.

So, if Japanese labor law protects foreigners and Japanese equally, what’s the problem? Let’s look at the Tokyo Kokusai Gakuen case (Tokyo District Court, March 15, 2001).

The defendant was a language school that employed the 16 plaintiffs in the case (of whom three were Japanese) as teachers. The case centered on claims of unpaid wages and security of contract renewals.

The foreign teachers were employed on a separate contract to the Japanese teachers (the contract was called the “Foreigner Contract”). The difference between the two contracts was that the one the Japanese instructors were on was permanent, whereas the foreigners were on fixed-term contracts. The plaintiffs alleged that this difference violated the aforementioned equal-treatment principle.

On this point, the court ruled against the teachers, finding that “the difference in contracts did not violate Article 3 of the Labor Standards Act” — the reason being, the court said, that “foreign teachers were employed as temporary, semi-regular staff and were given higher pay to compensate for the difference. The school did not discriminate in any other way.”

In other words, the court found that since the foreigners had no corresponding complaint about being paid more than Japanese in the same work, then it was not discriminatory for foreigners to be denied permanent employment.

This finding brings to mind the attitude that my Japanese friends had with regards to the ANA commercial: Sure, foreigners get a ribbing, but the racial traits exaggerated in the ad are desirable to us, so it can’t be racist. In a similar vein, according to the Tokyo District Court ruling, foreigners are on fixed-term contracts but they get paid more, so it can’t be discrimination.

I cannot agree with the court’s reasoning. High pay doesn’t make limiting foreigners’ term of employment fair. Isn’t it in principle discriminatory that Japanese are automatically put on lower-wage permanent contracts, and foreigners are automatically put on higher-wage limited-term contracts, completely disregarding the wishes of any of the individuals concerned?

Why is it that just because you are a foreigner, permanent employment is automatically off the table? And why does higher pay justify limited-term contracts? No rational reason comes to mind.

I think the principle of equal treatment established in Article 3 of the Labor Standards Act is a wonderful thing. The reality, however, is that constant violations of the principle persist in Japanese workplaces to this day.

It is important, now more than ever, for working people to fight for all workers’ rights to equality and security at the workplace. This is not something employers should be able to use to divide their employees. Instead of pandering to the grotesque caricature of globalization in ANA’s ad, employees would be better off heeding the global call of “Workers of the world, unite!”

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union (Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union). She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. On the second Thursday of each month, Hifumi looks at cases in Japan’s legal history to illustrate important principles in labor law.