Le Syndicat des Employés de l’Institut (SEI) de l’Institut Français du Japon à Tokyo, branche de Tozen, a adressé à la direction de l’Institut Français du Japon (IFJ), un avertissement d’entrée en dispute officielle, qui prendra effet le 26 février 2016 au soir, si la direction ne revient pas sur ses projets de précarisation générale des conditions de travail. La dispute officielle au Japon est l’étape légale nécessaire pour pouvoir conduire des actions syndicales telles que manifestations, tractages et grèves.

厚生年金未加入200万人、79万事業所調査へ

塩崎厚生労働相は13日の衆院予算委員会で、厚生年金に加入する資格があるのに未加入になっている人が約200万人に上るとの推計を明らかにした。塩崎氏は「(本来は)厚生年金に入れるのに国民年金であるならば大変な問題だ」と述べた。

Tozen Union wins victory over JCFL

The Tokyo Labor Commission ruled Monday morning that Japan College of Foreign Languages (JCFL, a division of Bunsai Gakuen) had illegally interfered with Tozen Union’s leafleting actions in front of the school. Tozen Union and its JCFL Local claimed that management sent employees out to block the union from passing out leaflets and made the union look bad.

The commission ruled in favor of the union, ordering management to cease all such interference and to post a large sign apologizing to the union at the workplace for ten days.

The victory was thanks to the relentless struggle of the local.

2 mil. employees not ‘nenkin’ enrolled

9:25 pm, January 14, 2016

Jiji Press

TOKYO (Jiji Press) — The Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry will launch a probe to identify companies neglecting their obligation to have employees join the appropriate public pension scheme, officials have said.

A ministry survey has found that an estimated 2 million people have not joined the “kosei nenkin” scheme for corporate employees even though they are legally required to do so. These people stay in the “kokumin nenkin” program for other people, including the self-employed, instead.

In Japan, incorporated businesses and sole proprietors who employ five or more people are obliged to have their workers join the corporate pension program.

Under the kosei nenkin scheme, employers cover half of the employees’ pension premiums. The workers participating in the program will be entitled to extra benefits that add to the basic pension provided under the kokumin nenkin program.

Graduates needn’t be hostages to advance contracts

The seniors I teach at Sagami Women’s University have already handed in their final dissertations and now await graduation in March. You can feel that a heavy burden has been lifted from their shoulders: “My friends and I are going to Fiji for our graduation trip”; “I’ve already reserved the traditional gown I’m going to wear to the graduation ceremony.”

In April they will go out into the world as shakaijin, or full-fledged adult members of society. As I’ve mentioned before, graduation and finding employment are seen as a single event in Japan. Students at university weigh up their strengths and interests, research the industry they aspire to join, perhaps do an internship, and then apply and interview for jobs. This whole process is called shūkatsu.

If an employer says they want you to start next April, then that is effectively an official promise of employment, or naitei. In a previous column, I explained that the employer is, in a sense, legally bound by the naitei, but today I would like to discuss the obligations of the prospective employee.

All of my current students have already received their naitei from assumed future employers. Many companies insist that students affix their personal seal to a written pledge to work for them.

残業ヤダ!って言ったらクビ?!

昔から今に至るまで、テレビドラマにはいろいろな「お決まりのシーン」がある。たとえば、朝、慌てて家を飛び出すヒロイン、通りすがりの男性に思いっきりぶつかり「あ、ごめんなさい~」と顔を赤らめながら立ち去ったときに、うっかりアクセサリーを落としてしまう。そして数日後、たまたま入ったカフェ。向かい側に座っているのは・・・あ、あのときの・・・そして、ロマンスが始まる、というパターン。(注:ここで落とすのはアクセサリーに限らず、財布や定期券などもポピュラー)

Japan’s culture and courts need to get with the program on overtime

TV series have for decades now overused a broad range of formulaic plot devices. Let me give you an example:

The heroine scrambles to get out of the house in the morning on her way to work. She runs down the street only to collide with a man walking the other way. Blushing, she showers him with apologies and in all the kerfuffle, a piece of jewelry slips off to the ground unnoticed. Days later she runs into him (figuratively this time) in a chic cafe, and romance brews. For variety, replace jewelry with wallet, train pass or other item; stir and bake.

For Japan’s English teachers, rays of hope amid the race to the bottom

The major economic engines of Japan Inc. — car manufacturers, appliance giants and the like — have often been caught price-fixing: colluding to keep an even market share, squeeze competitors out and maintain “harmony.” Similarly, the commercial English-teaching business could be accused of wage-fixing: Rather than competing for talent, they have followed one another’s lead, driving down salaries to hamper career development, limit job mobility and keep foreign teachers firmly in their place.

We’ve all heard the tale of the scorpion and the frog. In a rising flood, the scorpion asks the frog for a piggy-back ride across the river. The frog refuses, complaining that the scorpion will sting it to death midway. The scorpion assures the frog it would do no such thing because they would both drown. The frog accepts the logic, lets the scorpion on its back and begins to swim.

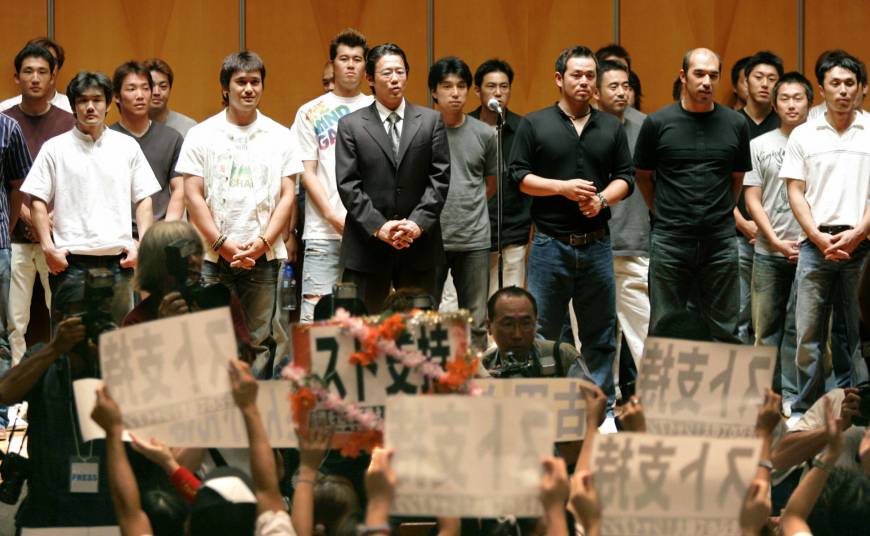

Lessons in Japan’s labor laws from striking NPB baseball stars and English teachers

Eleven years ago, baseball players walked off the field in protest for the first time in the seven-decade professional history of the game in Japan.

Owners wanted to consolidate two of the dozen pro teams, without offering a replacement. Players opposed the merger and were outraged that they had been kept out of the decision-making process. Atsuya Furuta of the Tokyo Yakult Swallows led collective bargaining on behalf of the Japan Professional Baseball Players Association union. Talks broke down and players struck six scheduled games over two days.

Players reached out to their fans with signing and photo events. Most fans sided with the striking players, but a vocal minority accused them of selfishness and having insulted their fans.

It always strikes me as odd how striking workers — rather than stubborn bosses — are often the ones accused of greed. The players did not take the decision to strike lightly; they had agonized over the decision and certainly were not taking their fans for granted. They made impassioned appeals to the fans that a strike was the only way they could save the wonderful spirit of the game.

改めて考える・・・「労働者にとってのストライキ」〜ストライキにどこか「罪悪感」を感じているすべての人へ〜

今から11年前、日本のプロ野球は、日本プロ野球球団設立以来初めてのストライキを行った。当時最大規模の「球界再編」が行われようとしていたが、その決定のプロセスのなかに「選手」は入っていなかった。自分たちのことなのに、なぜ自分たちが外されているのか…? 我慢ができなかった選手たちは、当時の選手会会長である古田敦也(ふるた あつや)氏を中心に、何回も団体交渉を重ねたものの、交渉は決裂。そしてついに、開催予定だった6つの試合でストライキが決行された。

ストライキは2日に及んだが、この間、選手たちは自主練習をしたり、ファンとのふれあいのイベント(サイン会や写真撮影会)を開催したりしていた。彼らのストライキに対しては、ほとんどのファンがストライキを支持し応援していたものの、なかには「ファンをないがしろにしている」、「自分たちだけよければいいのか」といった非難もあった。選手たちはおそらくこうした声を重く受け止めていたのだろう。彼らは、ストライキが苦渋の果ての決断であったということ、そして、決してファンを軽視するものではなく、むしろファンにとってより楽しいプロ野球にするためにも、ストライキが不可避であるといったことを、一生懸命にアピールしていた。