Pour pouvoir répondre sur la question de vos droits en tant que salarié au Japon, l’ADFE organise une conférence à l’ambassade à Tokyo. Inscription gratuite.

Uncategorized

「ちゃんと休ませてくれ!」―労働法における「休憩」って?

労働法と一言でいっても、そのなかには、さまざまな個別のテーマがある。たとえば、賃金、労働時間、配転、人事評価、解雇、営業譲渡、労働災害などなど。そのなかでも、あまり重きを置かれていないものに「休憩」がある。労働法の体系書を見ても、「休憩」に割くページ数は、他のテーマに比べるとかなり少ない。そもそも「労働」法とは、まさに「働くこと」がメインの法律なのだから、その対極にある「休むこと」については、あまり重視されていないのだろうか?

Next Court Hearing against ICC

Our next court hearing against ICC language school will be held on August 26 at 13:10 room 502 at Yokohama district court. It wil be the last hearing, exchange of documents. In September testimonies will start.

Although it’s in the middle of the day and far please try to come if you can. Thank you very much.

ICC外語学院を相手取った次の法廷での審理は8月26日13時10分、横浜地裁502号法廷です。 最後の審理と書面のやり取りになる予定です。 9月からは口頭陳述が始まります。

平日の日中の開催でしかも遠方ですが、可能ならばぜひお越しください。

どうもありがとうございました。

Five-Year Rule Seminar

Does new Labor Contract Law mean five years and out? Or five years and in?

「5年ルールセミナー」開催します!

◆ Date:日 時

Sunday, December 1, 2013 2:00pm to 5:00pm

2013年12月1日(日)午後2時00分〜午後5時00分

No entrance fee! 参加はどなたでも無料です。

Union, business concerns put limits on freedom of speech by Hifumi Okunuki

Hot on the heels of their romp to victory in the race for control of the House of Councilors, the Liberal Democratic Party is chomping at the bit to overhaul the Constitution, which has not been amended since it was signed into law in 1946. The ruling party proposes gutting Article 9, which forever bans war, and laying the legal groundwork for an official national military.

Today I won’t address this folly; rather, I’d like to discuss the tension between employees’ danketsuken (right to solidarity) and employers’ right to free speech under the as-yet-untweaked Constitution.

Article 21 guarantees without condition all freedom of “assembly, association, speech and publication.” All these freedoms apply to employers as well as employees.

Article 28 guarantees danketsuken: “The right of workers to come together in solidarity and to bargain and act collectively is guaranteed.” Together these are known as the three labor rights (rōdō sanken): danketsuken, dantaikōshōken and dantaikōdōken — the right to solidarity, to collective bargaining and to strike.

The Trade Union Law was built on the foundation that is Article 28. That law’s Article 7.3 prohibits interference (shihai kainyū) in the operation of a union by management. What this means in practice is that management’s freedom of speech is restricted to the extent that it interferes in the running of a union.

So when does an employer’s speech constitute illegal interference?

The most famous case to address the tension between an employer’s freedom of speech and the prohibition on union interference is the Prima Meat Packers case. The company had a closed shop, meaning membership in the union was a condition of employment and leaving or being expelled from the union meant automatic dismissal from the firm.

The union had bargained collectively several times over a wage demand during the spring labor offensive known as shuntō. After rejecting management’s latest offer, the union declared that talks had broken down.

The company president responded by sending the following memo to all employees:”It is unclear how union executives assess the company’s sincerity, but the union has announced the breakdown of talks. I believe this indicates an imminent strike. To me this seems like nothing more than striking for the sake of striking. This is quite regrettable. It is absolutely impossible for the company to raise its offer, so we are now have no choice but to take a drastic measure. I urge that both sides act in moderation.”

This document caused quite a kerfuffle in the union, with many members getting cold feet about striking. In the end nearly 200 members crossed the picket line.

The union sued for redress in the Tokyo Labor Commission, claiming the president’s message constituted interference in the union, discouraging members from striking and thereby violating Article 7.3 of the Trade Union Law. Both the Tokyo commission and then the National Labor Commission ruled in the union’s favor. The company dragged the case to court, but both the district and high courts upheld the Tokyo commission’s ruling.

Undeterred, management appealed to the Supreme Court. On Sept. 10, 1982, this fifth adjudicating body upheld all four lower rulings, handing workers a powerful judicial precedent.

The court’s reasons (ruling in italics):

1. While employers’ right to free speech is indeed protected by Article 21 of the Constitution, that right must be restricted by the prohibition on violating the danketsuken (right to solidarity) protected in Article 28.

The “right to solidarity” might sound strange to those who grew up in other countries, since it seems to imply a right to a feeling. In Japan, however, danketsuken is inviolable and trumps even free speech.

2. The content, method and timing of speech, the position and rank of the speaker, and the impact of the speech on union members, union organization or operation, when all considered together, determine that interference (shihai kainyū) has occurred.

The courts here again give themselves extraordinary latitude in deciding what is against the law, indicating that each case must be considered separately by each court.

3. Although the document was addressed to “employees,” it was effectively addressed to “all union members” since the company had a closed-shop agreement with the union. By criticizing the union leadership, there was a danger that the letter could drive a wedge between the executive and rank-and-file membership. The “drastic measure” had a menacing quality toward the union members. The call to “act in moderation” discouraged members from striking.

The court concluded that the document interfered with the independent operation of the union, including the decision to strike. (If I were of the management persuasion, I’d commend their persistence in appealing the first labor commission decision — no less than four times!) Ever since, the courts have consistently ruled that free speech does not extend to union interference.

Now let’s take a look at the other side of the coin.

The Supreme Court ruled on Dec. 20, 1983, in favor of a manager at Shinjuku Post Office who, at his own private home, spoke with employees and criticized the existing union’s militancy, while encouraging the employees to join a second union that was about to be formed. The court said, “The action might not have been fair, but it does not constitute union interference.”

On Dec. 21, 1970, Tokyo District Court likewise defended Oita Bank’s right to publish an internal newsletter describing the bank’s wage policies right in the middle of wage talks. The court said the bank was merely stating its opinion and was in no way committing shihai kainyū.

In the U.S., the right to free speech, protected by the First Amendment of that country’s Constitution, trumps both union and business rights. Thus, Target and other retailers are permitted to show their workers slick, professionally made infomercials with good-looking actors warning about how much unions will hurt workers (Google “Target’s Anti-Union Propaganda Video” and check it out). U.S. businesses openly hire anti-union consultants to bad-mouth unions to their hearts’ content, as long as they don’t engage in quid pro quo threats or promises tied to union membership.

In Japan, the situation is the reverse: Union and business rights both trump freedom of speech. This means that certain things management might say about a union at the workplace are illegal because they might discourage workers from joining or encourage them to leave the union, discourage them from striking or encourage them to scab, etc. The aforementioned Target video would be flagrantly illegal in Japan.

The labor laws in each country reflect their different histories, structure, ideology and social norms. I will leave you to decide which system is fairer, but I would suggest that management has overwhelmingly more intrinsic financial, positional and propaganda power than the average labor union.

I would be interested to know to what extent our readers think that freedom of speech should be protected. Should it trump union rights?

Five-Year Rule Seminar

有期労働契約の新たな“5年ルール”とは

〜5年でGood byeってホント?〜

Five-Year Rule Seminar

Does new Labor Contract Law mean five years and out? Or five years and in?

新しい労働契約法についてのセミナーを開催します!

日 時:2013年7月7日(日)Sunday, July 7, 2013 2pm to 5pm

午後2時00分〜午後5時00分(途中10分休憩あり)

☆参加無料! No entrance fee!

講 師:Instructors: Attn. Shoichi Ibuski (Akatsuki Law Firm)

指宿 昭一弁護士(暁法律事務所)

Hifumi Okunuki (Executive President of Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union/

Teaches at Sagami Women’s University)

奥貫 妃文(全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオン執行委員長、相模女子大学専任講師)

今年から、労働契約法に有期労働契約に関する3つのルールが新たに加わりました。

This year Labor Contract Law added three new rules for fixed-term employment.

☆Point1.有期労働契約の期間の定めのない労働契約への転換(いわゆる「5年ルール」の新設)

Fixed-term contracts switch to permanent employment after 5 years

☆Point2.有期労働契約の「雇止め法理」の法定化

The law codifies rules for refusal to renew fixed-term contracts

☆Point3.有期労働契約であることによる不合理な労働条件の差別禁止

The law prohibits illegitimate discrimination against fixed-term employees

今回の法改正は、現在、実際に有期で働く人たちにどのようなインパクトを与えるのでしょうか。とくに、大学で有期で働く先生たちは、5年になる前に契約を打ち切られてしまうのではないかという大きな不安を抱いています。また実際に「契約は3年まで」、「更新はしません」といった文言を募集要項に掲載する大学も、ちらほら見られるようになりました。

What impact will this have on those currently working fixed-term contracts? Particularly teachers at universities are worried they might be non-renewed before reaching the five-year mark. Some universities are already putting out want-ads announcing the post is only for three years and will not be renewed.

しかし、不安ばかりではどうにもなりません。まずは、この法律の趣旨をしっかりと理解したうえで、どのように「安定した雇用」を権利として求めていくべきなのか、そして、具体的にどのような闘い方をすればいいのか、このセミナーでみんなで考え、知恵を出し合っていきましょう。そして、有期労働契約で働く友人、知人のみなさんにも、ぜひ、このセミナーに一緒に参加しようと声をかけてください。

Anxiety alone will solve nothing. First let’s find out precisely what the new law says, how we can pursue the right to job security and specifically how to fight. This seminar will provide a chance to put our heads together and prepare. Please bring your friends, acquaintances and anyone else who works on fixed-term contracts to this seminar.

なお、このセミナーでは特に顕著な影響が出ている大学の非常勤講師の問題を多く取り扱う予定ですが、もちろん、有期労働契約はすべての労働者に共通する問題です。すべての業種の人たちにご参加いただければと思っています。

We will focus in particular on university part-time teachers, who will be particularly impacted by this change, but of course the problem is shared by all workers on such contracts and all are very welcome.

◆ プログラム Program

1 有期雇用労働者と労働法〜これまでの法制度と今回の改正について(指宿昭一弁護士)

Fixed-term employees and labor law. The law ’till now and the new amendment. (Attn. Shoichi Ibuski)

2 質疑応答 Q&A

3 大学の非常勤講師をめぐるこれまでの労働判決と最近の動向(奥貫妃文)

Case law and recent trends for part-time instructors at universities. (Tozen President Hifumi Okunuki)

4 質疑応答 Q&A

〜10分休憩〜 10-minute break

5 会場の実態報告&ディベート 〜今後、法改正に対してどう対処すべきか〜

Workplace reports from the floor and debate. What is to be done?

6 「有期労働契約実態調査」記入のお願い

Please answer our questionnaire on your fixed-term employment

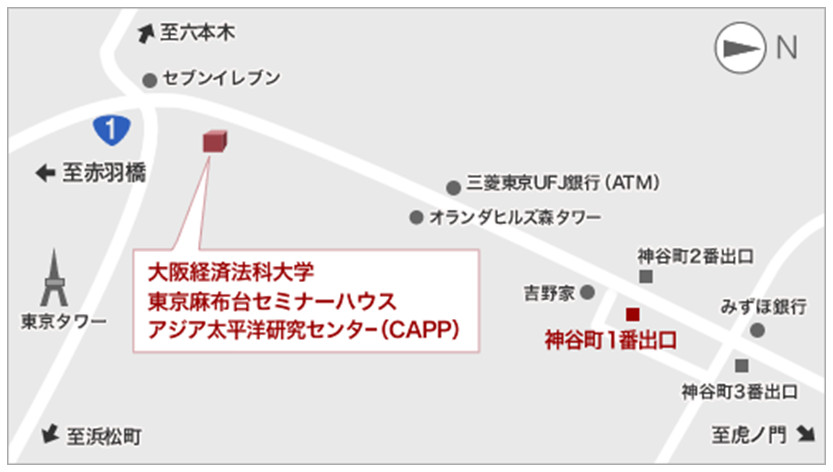

◆ 場 所 Venue : Osaka Keizai Hohka Daigaku Tokyo Azabudai Seminar House

〒106-0041 Tokyo, Minato-ku, Azabudai 1-11-5, Tokyo Azabudai Seminar House

* Take Hibiya Line to Kamiyacho Station, Exit 1. Then a five-minute walk.

(TEL:03-5545-7789 E-mail:capp@keiho-u.ac.jp )

5年ルールセミナーパンフレット(日本語)

有期労働契約の新たな“5年ルール”とは?

〜5年でGood byeってホント?〜

新しい労働契約法についてのセミナーを開催します!

日時:2013年7月7日(日)

午後2時00分〜午後5時00分(途中10分休憩あり) ☆参加無料

講師: 指宿 昭一弁護士(暁法律事務所)

奥貫 妃文(全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオン執行委員長、相模女子大学専任講師)

今年から、労働契約法に有期労働契約に関する3つのルールが新たに加わりました。

☆Point1.有期労働契約の期間の定めのない労働契約への転換

(いわゆる「5年ルール」の新設)

☆Point2.有期労働契約の「雇止め法理」の法定化

☆Point3.有期労働契約であることによる不合理な労働条件の禁止

今回の法改正は、現在、実際に有期で働く人たちにどのようなインパクトを与えるのでしょうか。とくに、大学で有期で働く先生たちは、5年になる前に契約を打ち切られてしまうのではないかという大きな不安を抱いています。また実際に「契約は3年まで」、「更新はしません」といった文言を募集要項に掲載する大学も、ちらほら見られるようになりました。

しかし、不安ばかりではどうにもなりません。まずは、この法律の趣旨をしっかりと理解したうえで、どのように「安定した雇用」を権利として求めていくべきなのか、そして、具体的にどのような闘い方をすればいいのか、このセミナーでみんなで考え、知恵を出し合っていきましょう。そして、有期労働契約で働く友人、知人のみなさんにも、ぜひ、このセミナーに一緒に参加しようと声をかけてください。

なお、このセミナーでは特に顕著な影響が出ている大学の非常勤講師の問題を多く取り扱う予定ですが、もちとん、有期労働契約はすべての労働者に共通する問題です。すべての業種の人たちにご参加いただければと思っています。

◆プログラム

1 有期雇用労働者と労働法〜これまでの法制度と今回の改正について(指宿昭一弁護士)

2 質疑応答

3 大学の非常勤講師をめぐるこれまでの労働判決と最近の動向(奥貫妃文)

(早稲田大学、大阪大学等)

4 質疑応答

〜10分休憩〜

5 会場の実態報告&ディベート 〜今後、法改正に対してどう対処すべきか〜

6 「有期労働契約実態調査」記入のお願い

7 おわり

◆場 所:大阪経済法科大学麻布台セミナーハウス

〒106-0041 東京都港区麻布台1-11-5東京麻布台セミナーハウス

地下鉄日比谷線神谷町駅出口①から徒歩5分

地図:http://www.keiho-u.ac.jp/research/asia-pacific/access.html

Precedent backs (nearly) equal pay for equal work

In 2012, Japan had 51.73 million workers, of which 33.3 million were regular employees, or seishain, according to the latest survey by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Contingent, or nonpermanent, workers (including part-timers, haken dispatch and shokutaku semiregular employees) numbered 18.43 million, over 35.5 percent of the workforce.

When I first began studying labor law in graduate school over a decade ago, contingent workers (hiseiki rōdōsha) were a peripheral phenomenon, but today they form a central pillar of Japan’s workforce.

So what’s wrong with being a contingent worker?

First of all, most have temporary or fixed-term contracts, which translates into roughly zero job security. Despite it being mandatory, many employers fail to enroll their contingent employees in Japan’s shakai hoken health and pension scheme. This raises anxiety among workers about what will happen when they get ill or old.

The biggest problem, however, is wage differences between nonpermanent and seishain employees. For example, these days we see ever more supermarkets and food companies employing low-wage shop managers, posts that were once held exclusively by seishain. They make, say, ¥900 an hour with no bonus and no severance pay. Their responsibilities and hard work are on par with those of the seishain they work with, but there the parity ends. Today, contingent workers make Japan’s industrial world go round.

But is this situation fair or even sustainable?

Labor law says little about discrepancies between the conditions of seishain and contingent workers. Article 3 of the Labor Standards Law prohibits discrimination based on “social standing,” but courts have already interpreted this phrase to exclude employment status. Article 8 of the Part-time Worker Labor Law, enacted in 1993, prohibits discrimination, but “part-timers” affected by the law are limited to those who have open-ended employment, do the same jobs as seishain and are dealt with the same manner as ordinary workers. (Pāto in Japanese has a far broader meaning than “part-time” in English and often includes full-time temporary or other contingent employment.) Few if any part-time workers satisfy such conditions, making the law little more than e ni kaita mochi, or “rice cakes in a painting,” as the saying goes. (In other words, like “pies in the sky,” you can’t eat ‘em.)

The most famous legal challenge to disparities between the two types of workers came in the mid-1990s. Twenty-eight women working on recurring two-month contracts for an auto parts company mustered their courage, unionized and challenged their wage disparity with their seishain colleagues in Nagano District Court. Despite flimsy legal grounding, they asked the court to order the employer, Maruko Keihoki Co., to pay wages lost due to pay that was far less than their seishain coworkers, despite the fact they worked the same production line, did the same job and clocked in on the same hours and days.

Seishain regular workers were paid a basic monthly wage that increased in line with seniority, while the “two-monthers” received daily wages amounting to 60 percent of the average of their seishain coworkers. The plaintiffs asserted that getting lower pay for the same work violated the principle articulated in Article 90 of the Civil Code called kōjo ryōzoku, or public order and morality.

Leading labor law scholars sounded off against the claim, saying Japan has no legal principle of equal pay for equal work and that the court should refuse redress. The claimants’ chances looked dim.

On March 15, 1996, however, the gods smiled down on the Maruko Keihoki 28, with the court ruling that “although equal pay for equal work cannot be considered itself a requirement of public order and morality, the principle is reflected in the two pay-parity provisions (Articles 3 and 4) of the Labor Standards Law and should be a universal value of a society that treats all as equal under the law. Any wage disparity that violates this principle goes beyond the legitimate discretion of the employer and therefore violates public order and morality.”

The judge then ruled that any wages falling below 80 percent of the equivalent for seishain must be repaid to the plaintiffs. This arbitrary threshold baffled commentators, as the court was in effect saying wage disparity is wrong on the one hand, but that 20 percent was fine and dandy.

Maruko Keihoki appealed and the parties settled in what is rightly considered a complete victory for the plaintiffs. The deal included a change from daily to monthly wages, repayment of the disparity in wages, summer and winter bonuses equal to those of seishain staff, and identical severance packages upon leaving the company.

This was the first ruling to recognize wage disparity between the two types of workers as a violation of public order and morality, or kōjo ryōzoku. Despite the mixed message, it is hard to overestimate the impact this verdict has had on later rulings.

The plaintiffs had no specialized labor law knowledge and they fought while caring for their families. Their unifying gripe was the injustice of doing the same work and hours for two-thirds of the pay of their colleagues. Their simple rejection of this indignity inspired them to fight on.

An uplifting addendum to this anecdote is that the seishain at Maruko Keihoki fought arm in arm with the plaintiffs. One regular worker said: “We were astonished when we heard the wages of these women who work right next to us. We thought it was unacceptable and that we had to fight alongside them to rectify it.”

This labor union brought together regular and irregular staff in the fight for equal pay. Lest we forget, this landmark victory was born of worker solidarity that transcended employment status.

by Hifumi Okunuki

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2013/05/21/issues/precedent-backs-nearly-equal-pay-for-equal-work/#.UZ2p4r-ElZI

New law: no dues, no visa

An article from July that concerns every foreigner working in Japan.

Are you enrolled in Shakai Hoken or did Interac tell you you weren’t eligible? Are you going to have to pay up to two years of back pay into the system next year because Interac/Maxceed did not register you into the system when you started working for them?

Let’s hope not.

Solidarity

http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20090728zg.html

By JENNY UECHI

Enrollment in Japan’s health insurance program tied to visa renewal from 2010

By JENNY UECHI

In your wallet or somewhere at home, do you have a blue or pink card showing that you are enrolled in one of Japan’s national health and pension programs? If not, and if you are thinking of extending your stay here, you may want to think about a recent revision to visa requirements for foreign residents. The changes, which the Justice Ministry says were made in order to “smooth out the administrative process,” may have major consequences for foreign residents and their future in Japan.