Interac teachers in Kanto enter second round of collective bargaining. They’re demanding full-time permanent employment, shakai hoken, a 20% pay raise, a ¥600,000 yearly bonus, a time card, a prior consultation agreement, and a union page on the Interac employee website.

ALTs

Why Japanese people keep working themselves to death

TOKYO — Years after losing his son, Itsuo Sekigawa is still in shock, grief-stricken and angry.

Straight out of college in 2009, his son Satoshi proudly joined a prestigious manufacturer, but within a year he was dead. Investigators said working extreme hours drove him to take his own life.

The young engineer fell victim to the Japanese phenomenon of “karoshi,” or death from overwork.

Shakai hoken shake-up will open up pensions for some but close door on benefits for others

June 6, 1980, was a Friday. The Social Insurance Agency quietly issued an untitled internal memo called a naikan regarding the eligibility of part-timers in Japan’s shakai hoken health and pension program. Who could have known what chaos, confusion and frustration that single-page document would cause in the coming decades? Let’s get our hands dirty and dig through the details.

For Japan’s English teachers, rays of hope amid the race to the bottom

The major economic engines of Japan Inc. — car manufacturers, appliance giants and the like — have often been caught price-fixing: colluding to keep an even market share, squeeze competitors out and maintain “harmony.” Similarly, the commercial English-teaching business could be accused of wage-fixing: Rather than competing for talent, they have followed one another’s lead, driving down salaries to hamper career development, limit job mobility and keep foreign teachers firmly in their place.

We’ve all heard the tale of the scorpion and the frog. In a rising flood, the scorpion asks the frog for a piggy-back ride across the river. The frog refuses, complaining that the scorpion will sting it to death midway. The scorpion assures the frog it would do no such thing because they would both drown. The frog accepts the logic, lets the scorpion on its back and begins to swim.

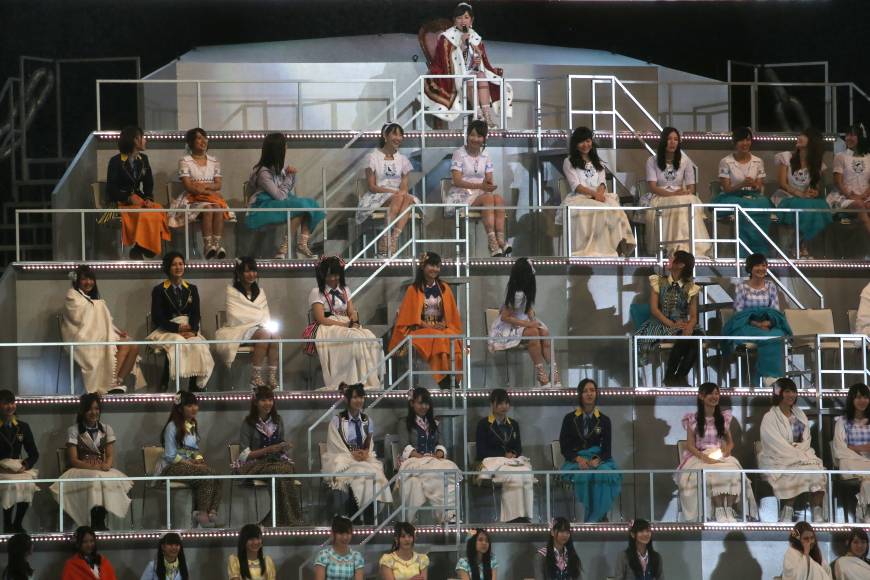

AKB48 members deserve to get workers’ comp for saw attack

On May 25, a man wielding a saw attacked and wounded 19-year-old Rina Kawaei and 18-year-old Anna Iriyama, two members of bumper girl group AKB48, and a male staffer at an event where fans get to shake hands with their AKB idols.

Fortunately the injuries were minor, but fans were shocked. The victims and their AKB48 comrades must have been terrified.

Demands submitted to Interac/Maxceed concerning Drug Testing

株式会社インタラック 御中

株式会社マクシード 御中全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオン

執行委員長ルイス・カーレット

全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオン

東ゼンALT支部

執行委員長アムジッド・アラム

緊急団交申し入れ Emergency Request for CB

全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオン(略称:東ゼン)ならびに全国一般東京ゼネラルユニオン東ゼンALT支部は、貴社に対して、緊急団体交渉を申し入れます。貴社は先日、当組合員らを含む従業員らに対して、薬物検査を受けるよう指示したと伺いました。薬物検査は、通常の雇用関係においてはこれを行う必要性が認められず、よほどの事情がない限り、従業員に広く行われるものではないはずです。昨今の個人情報保護の重要性に鑑みても、安易にこのような検査を実施することに対して、大きな疑問を抱きます。

つきましては、下記の議題にて団交を実施したく存じます。

Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union (“Tozen”) and Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union Tozen ALTs request emergency collective bargaining. We have heard that you instructed your employees, including union members, to undergo drug testing. The need for drug testing is not accepted for an ordinary employment relationship and drug testing of employees in general is accepted only in extreme circumstances. We strongly oppose your casual testing of employees also in light of recent requirements to protect individual privacy, including the passage of Individual Information Law, We therefore ask for cb with the agenda stated below.

記

An Immigration Stimulus for Japan

Allowing in more foreign workers would boost growth, especially in quake-ravaged areas.

Recent economic data showed that Japan was slipping into recession even before the devastating earthquake and tsunami of March 11. In the aftermath of that natural disaster, putting the country back on an economic-growth track is doubly important as the government and businesses try to finance reconstruction. Given the urgency of the challenge, any and all pro-growth policy options should be on the table. That includes a controversial but important measure: immigration reform.

Population is a central problem confronting Japan. A falling birth rate and an aging population mean that the country has far too few young, productive workers. This will become even more noticeable as the current working generation begins to retire. Unless radical policies are implemented, it is simply a matter of time before manufacturing, consumption, tax receipts, fiscal health, the pension and welfare system, and the very ability of people to make a living will all collapse under the inexorable dual pressures of rapid aging and rapid declines in the young working population.

The only solution is to import more workers. I estimate that Japan needs to welcome some 10 million immigrants over the next 50 years to avoid the negative consequences of population decline. That would bring immigrant numbers to about 10% of the population, the level in the U.K., France and Germany.

Such numbers would spur growth because new markets and demand would arise for clothing, food, education, labor, finance, tourism and information. Robust immigration policies would encourage foreign investors to reassess long-term economic prospects, starting another virtuous cycle of interaction with the outside world.

Immigration will be critical to reinvigorating Japan’s most important industries. Take farming: The farming population of Japan declined by 750,000 between 2005 and 2010, bringing it to merely 2.6 million, according to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The average age of a farmer is 65.8 years.

This makes it a certainty that in 10 years, the farming population will decline by roughly half. The fishing industry faces the same fate. The population of fishermen and the volume of their catches are headed in the same direction: down, rapidly.

This demographic trend was already afflicting areas such as the rice-growing areas in Miyagi Prefecture that are now reeling from the March 11 disaster. Unless radical reform is implemented, the decline will only accelerate as older farmers balk at rebuilding and younger workers continue to flee. It will simply not be possible to rebuild local industries using only Japanese employees that have only a few more years in the workforce left.

Nor is the list of regions in need of immigration confined to those affected by the disaster. Aichi Prefecture, the heart of Japanese industry and home to iconic companies such as Toyota, is a case in point. The population that supported the economy in these areas in the past has declined. For instance, in Aichi prefecture not only did the total population decline between 2000 and 2009, but the percentage of working-age persons (age 15-64) dropped to 65.5% from 69.8%. Similar rapid trends have affected Niigata Prefecture, a rice-growing center, and the Sanriku Oki area, one of the finest fishing grounds in the world.

The problem extends deeper than mere numbers of workers. One consequence of a shrinking population is that visionaries and risk-takers—entrepreneurs in business, politics, education, journalism and the arts—become scarcer and scarcer. That compounds the phenomenon that a society that was highly homogeneous to begin with has educated its people with standardized content in a culture that discourages too much free thinking. Lack of fresh faces makes the country seem increasingly sterile.

Because Japan has traditionally been such a homogeneous place, many have feared the prospect of greater immigration. Yet a pro-immigration policy doesn’t have to undermine Japanese values or culture. If policy makers have the will to encourage greater immigration, they can find ways to do it well.

The centerpiece of any immigration policy would be to ensure the country attracts highly skilled workers and provides them with a clear path to integrate into Japanese society. To start, Japan needs a total overhaul of its system for foreign students and trainees. Currently those students have few or no prospects for staying permanently. Only 30% of foreign students graduating from Japanese universities stay in Japan. That number must be closer to 70%.

Not only must the government do more to attract students in a wider range of fields, including vocational areas such as agriculture, but policy makers must make it easier for those workers to stay permanently. A country with a declining population does not need guest workers. This would involve simplifying the procedure for gaining permanent residency and even citizenship. At a minimum, any foreign worker in steady employment should be able to apply for permanent status.

In some respects, boosting immigration can seem like a daunting task. The government needs to reform the pension system to cover workers who immigrate in mid-career; landlords must be more willing to accept non-Japanese tenants; citizenship laws need to offer citizenship from birth to the children of immigrants. Policy makers also will need to work to change the culture within companies. For instance, foreign workers often are discriminated against in terms of salary and promotion opportunities. Government should press the private sector to end this sort of practice.

These reforms would be significant, but none would require sacrificing the best features of Japanese life. For instance, government should actively encourage immigrants to master the language—and everyone should remember that children born to immigrants likely will grow up fluent if we ensure they’re allowed to integrate into society. And despite caricatures of frightening or violent foreigners in the popular imagination, immigration won’t compromise public safety as long as Japan is attracting highly skilled, employed immigrants and allowing them and their families opportunities for social and economic advancement.

Japan must recognize that globalization is here to stay, and should stake its very survival on accepting people elsewhere in the world as its brethren, and transforming itself into a much more multicultural, diverse society. It will be a large task, but Japan is past the point where easy solutions will do.

Mr. Sakanaka is executive director of the Humanitarian Immigrant Support Center in Tokyo. He previously served as the Chief of Entry and Residence at the Nagoya and Tokyo Immigration Bureaus.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303714704576384841676111236.html

Interac Demo, Round 2

Over 15 members showed up Saturday morning for the second Interac demonstration. We played music (“You can’ get me cuz I’m in the union…”) and spoke for about 30 minutes, passing out our mark II Interac dispute newsletter.

We set the bullhorn again on the hillock opposite the company. Hundreds of students (probably on their way to Hosei University) passed by and the vast majority took flyers. We also took several poses, including a “j’accuse” stance with us all extending our arms and pointing to the Interac office in imitation of the Memphis balcony in the seconds after Martin Luther King’s assassination.

The day was hot but fun overall. Again the cops came (only one actually) and very politely asked us if we had a labor dispute and how long we would be. After we answered him, he left quietly.

Interac Demonstration

Each Saturday morning Interac offers free Japanese lessons to ALTs at HQ. So we were right back out there Saturday morning with our posters and fliers – this time 17 members. We figured surely Interac wouldn’t cancel an entire class just to avoid the union’s demonstration. Again we had underestimated Interac’s cowardice.

We set the bullhorn facing the firm on a hillock across the road. We spoke our grievances to the morning passers-by. We played an inspiring union song on a CD player that kept flaking out.

Three cops approached and began speaking to Yoko-the only Japanese member of our party. I stepped in, anticipating the usual official harassment. To my surprise, they were polite–even gracious. They asked us two questions: one, “Is this a labor-management dispute?”, and two, “How long will your demo last?” They were quite satisfied with our answers and casually strolled off back up the road.

GS Samantha made a stirring, personal speech, closing with an appeal to Interac to listen to us: “Kiite kudasai.”

Then we sent branch members and guards up to the second floor office-cheering them on. Back down the delegation reported that Interac staff were gone. We felt flattered that Interac would do us the great honor of showing their fear of us. Twice. We continued to pass out fliers accusing the Chairman, Seiichi Matsumoto, of wimpiness and breaking the law.

We finished off our 45-minute demo with a loud shprehicall and music.

This weekend was just the first step for our newest branch, but it was a big one.

Interac runs from collective bargaining

Unable after weeks to get Interac and its slippery Chairman Seiichi Matsumoto to agree to talks…or even to talk…even on the phone, Nambu Interac Branch and several other Nambu activists went to Interac HQ in Iidabashi Friday evening to demand collective bargaining.

We knew Interac HQ operates until 9pm so arriving at 7pm gave us plenty of wiggle room. When we reached the building, however, it was all locked up and the inside lobby was dark. Interac shares the building with several other firms so we were perplexed.

Stepping back we could see lights on the second floor. We pressed the button on the night intercom. Rain was falling steadily.

“Yeah.”

“This is the Interac union. We’re here for collective bargaining.”

“I didn’t hear anything about it. They all went home already.”

“We can see lights on their floor.”

And so it went – me and an unseen gruff man bickering about the right to pass. He refused to budge and cut the connection. Most of us knew of Interac management’s breathtaking cowardice – but were they such scaredey cats that they would hide in their office till 9? We later learned that they were scareder still.

Concerned that they might use an escape route, we sent a couple of scouts around to scour the base of the building for alternative exits. Garrett found a locked door at the top of a dark stairs.

We were just about to post a sentry there with a cellfone when from the darkness of the lobby a face appeared. Through the locked door he explained how to get to the garage which has an entrance. Being paranoid by nature I left a guard at the door in case the instruction was a ruse to decoy us away from the front door while Interac management snuck out.

The rest of us made our way to the garage entrance where a guard sat behind a desk and window. I prepared to confront him but he hadn’t noticed us so with mouth still poised to speak we walked by.

“Wait a minute. I can’t let you pass,” said a familiar voice.

Our right of passage – not really what this phrase means – evolved into a full-fledged debate: Greg proved he was an employee by showing his gaitoh-shoh (foreign registration card); the guard demonstrated that Interac had split by letting the phone ring.

Heated debate gave way to negotiations. I said let us go up and check the second floor. The guard agreed on condition that one person alone go and that I agree not to disturb any other company.

When the elevator doors opened I saw that Interac was indeed closed for business. Everything was dark, locked and brand new signs said, “No unauthorized personnel!” in Japanese and English. The lights we had seen from outside were at the company next door.

Back down at the underground garage level I conceded to the guard that Interac had left. The guard then made an admission of his own: “Well, they usually work till 9 but this evening they were in quite a hurry to leave by 6. They even asked me to hold a package that was to be picked up after they left.” The guard even apologized for his arrogance. I apologized and explained our predicament. I left my calling card.

So the entire HQ staff of the nation’s largest ALT dispatcher skedaddled out of work three hours early to avoid talking to five of their employees. I realized that Interac’s savvy anti-union strategy had a name: Operation Run-For-The-Hills.