On March 30, 2022, NHK Web News ran a story on how women driven to financial hardship due to the corona pandemic are increasingly turning to sex work. (https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20220330/k10013558231000.html)

The report notes that sex workers’ “growing presence in busy urban neighborhoods has spurred police to take enforcement action but also to assign case officers to provide support and to accompany the arrested women to life consultant centers run by local governments.” The cops have begun to provide support for the women’s futures from a social welfare perspective, rather than just cracking down.

Prostitution is illegal in Japan. Baishun (selling spring) violates the 1956 Anti-Prostitution Act. Baishun is defined as ‘having sexual intercourse with an unspecified person in exchange for compensation or the promise of such.’ Article 3 prohibits any person from engaging in or soliciting prostitution.

The unspecified (futokutei) in the definition refers to persons not in a particular relationship, so exchange of money for sex among lovers or spouses does not correspond to the legal definition of prostitution. The sexual intercourse includes only penetration by a sex organ, or homban in industry parlance, and does not include intercourse-adjacent behavior such as tekoki (hand job) or kōin (fellatio). Such acts are legal under the Act on Control and Improvement of Amusement Businesses.

Establishments are broken down into categories, such as soapland, deliheru, fashion-health, and pinsaro. Soapland refers to brothels with bathing facilities. Deliheru (delivery health) refers to a service that dispatches women to the client’s home or hotel to provide sexual services. Pinsaro (pink salon) are establishments specializing in fellatio.

Of these, soapland establishments charge the highest prices with a wink-wink tacit understanding that they offer even illegal homban acts. Soapland management maintains the tatemae pretense that services stop at intercourse-adjacent acts and that the establishment has no responsibility for any homban that might occur since it must have been the result of freely expressed affection between the sex worker and her client. That ensures that the relationship takes on a “specified nature” (i.e., that of lovers), enabling the soapland to skirt the law and continue to exist.

Law enforcement has chosen to look the other way, but it is within the realm of possibility that they might someday conduct a serious investigate that will result in mass arrests.

Sex work, kyabakura (female conversation companions), hosuto (male companions) and other mizushobai trades (entertainment, liquor and related businesses) are called yorushoku (nighttime trades), whereas ordinary jobs done during the day are called hirushoku(midday trades). The corona pandemic has driven countless women out of their day jobs and lowered the psychological resistance of women to take up nighttime trades.

But putting on glittery dresses, perfecting make-up and attracting male customers is a daily struggle. In this world of cutthroat competition, employers and clients incessantly assess and place a price tag on your appearance, age, and demeanor.

One host bar advertises that if a male host climbs to the number one spot, he can pull in 100 million yen a year. The ad encourages you to Become a 100-million-yen player! The reality is that many workers in the nighttime business end up drinking too much; destroying their physical and mental health in their dealings with clients, managers, and coworkers; driving them to ramp up their dependence on alcohol, drugs, gambling, and shopping.

Most workers in this industry are women, and as a fellow woman, my emotional response is that yorushoku entails dangers on many levels and is not a profession I can recommend to others. Particularly, sex work risks damaging not only your physical body but also your mental health.

Some commentators will respond that sex work is a proper occupation like any other, pointing out that day jobs often entail sexual harassment, power harassment, bullying and other cruelty. Many will insist that we should respect the occupation of women who chose sex work of their own volition and that treating sex work differently is a form of occupational discrimination.

It goes without saying that I respect the personal choices of adult women. But we also must consider if the working world is fair enough to women to enable them to make a truly autonomous decision. Is the working situation such that a women can make a living doing ordinary day jobs? Is the ordinary workplace such that she can raise small children while working in an office? Some women grow up suffering from parental violence, abuse and with no chance for a proper education. As adults, do they get educational, financial support and a chance for a stable job?

Some women grow up in affluent, loving families and receive proper education. Other than those fortunate few, it seems that women cannot effectively make autonomous life choices when presented with such a narrow range of options.

The human body and mind are more or less inseparable. I imagine sex workers must prepare themselves mentally so as to commodify their genitalia and most efficiently use it for business to earn remuneration. They must anesthetize and still their hearts in order to fulfill their work duties. This process often entails illegal drugs, and some women overdose. I don’t think a job should exist that requires such a suppression of our natural feelings and emotions.

Physical dangers cannot be ignored either. Last June, a deriheru worker in her 30s was murdered – stabbed over 70 times by a client in a love hotel in Tachikawa, Tokyo. This year, a woman in her 20s propositioned a man in his 80s in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, but ended up stabbing him to death with a box cutter after arguing over money. The sex worker was the victim in one case and the perpetrator in the other. But entering a hotel alone with a stranger carries such extreme risks.

Although official figures are unavailable, reports indicate that women working in this industry are more likely to have grown up in abusive families and to suffer from diagnosed mental or psychological disability. I wonder if those calling for sex work to be treated like any other occupation are aware of this reality.

In late March, I went to Osaka and interviewed many yorushoku workers. on their problems, worries and troubles. I also spoke with activists who provide support to such workers. And for the first time in my fifty years, I went to a host club. Many people think of host clubs as a place that sets you back several hundred thousand yen just to sit next to a dandy. But the club I went to offered a first visit for just about 1,000 yen, including all-you-can-drink.

For 70 minutes, 23 different men young enough to be my son rotated through to where I sat. Each host pleaded that I designate him by name on my next visit. They had spent a great deal of money on their suits, brand-name clothing, and took great pains to make themselves as appealing as possible in a desperate bid to reach the status of number one in the club. Their devotion and communication skills impressed me.

Hosts have a reputation for being kind of flashy, shallow, drunk, and rowdy, but my Osaka club experience suggests that maybe none of that is true. One host chuckled to me that he never remembers what happens after going home at night because he must drink until 1am. Another told me that his “toxic parents” refused to pay for him to go to high school and instead beat the hell out of him. He ran away from home and has not contacted them since.

With no home, he felt that the path of a host was the only one for him. I wondered if he would have chosen such a path if his teenage years had been different.

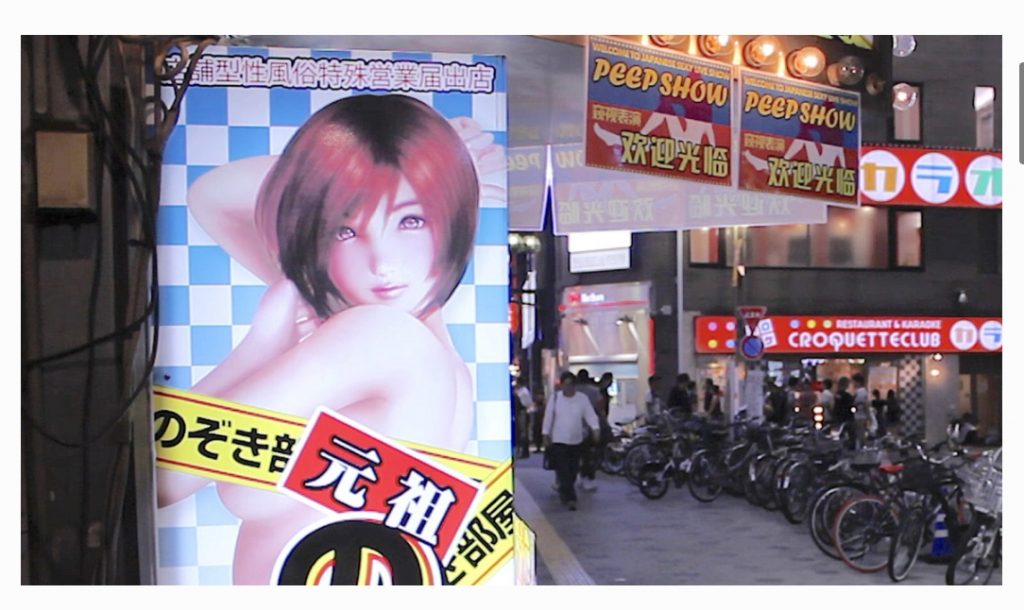

In Osaka, I visited the Tobitashinchi neighborhood, which was a famed red-light district during the Taisho Era (1912 to 1926) and is still in business. Women sit under dim lanterns in the entranceways of little, old homes, drawing in men who walk by. Once night falls, men begin to enter one after another. This district is famed for a place where a man can knock off a homban quickly with no fuss.

I walked through this district with a former sex worker in her 20s and an aid worker in his 30s.

The man said, “Tobitashinchi is just for homban, so the man doesn’t need to worry about talking or any personal communication. In terms of just doing what you came to do, this place is probably pretty attractive.”

The woman I was with said, “All the women who were in Tobitashinchi had dead eyes. Of course, because at the entranceway, they must focus only on selling themselves as pure commodities at the highest price possible. Reflecting on it might kill them.”

The pandemic has thrown more people into financial distress. And nighttime work has thrown open its doors wide to take in people struggling to make ends meet. As a society, we must ensure proper working conditions for those working yorushoku, reduce the associated dangers, and increase the number of choices available so women can make truly autonomous decisions.

This article was written by Hifumi Okunuki, and originally published by the Shingetsu News Agency (SNA).