Flabbergasted. That was my feeling last week reading the news of an example of brazen institutional sexism and fraud 33 years after the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law.

Each year since 2010, Tokyo Medical University fraudulently lowered the scores of female applicants who took the annual entrance exam, keeping the percentage of young women admitted at about 30 percent.

Only those who pass the school’s written multiple-choice exam can move on to the final short-essay-and-interview phase. The cap on number of admissions is set without reference to gender. This year 2,614 took the entrance exam, of which 61 percent were male and 39 female. The university took the women’s test scores and multiplied them by a coefficient less than 1 in order to reduce their scores across the board. This resulted in men comprising 67 percent of those passing phase one and 82 percent (141) of those passing both phases. Only 30 women (18 percent) managed to make it through to admission.

By 2010, the percentage of women gaining admission had skyrocketed to nearly 40 percent of the total. Many new female physicians leave the workplace for childbirth or child care, so some in the university apparently feared that too many women entering the ranks might lead to a dearth of qualified professionals. So some genius — a man, no doubt — had the bright idea of solving this problem by holding back women at the entrance exam stage. That is how the university has justified what it did.

The education ministry has stated: “A university can take responsibility for adjusting gender proportions if they make it explicit when they are recruiting for the entrance exams. If Tokyo Medical University made such an adjustment without explanation, then it is problematic.”

The media naturally have latched onto this issue since it came to light. Many people were angry and shocked. Women who failed this year’s entrance exam at the university wondered if they too had suffered from this unfair downgrade. They had spent so many sleepless nights, just like their male counterparts, studying to pass the test. Their efforts were betrayed.

Some spoke in anger, voices quivering. Even some male students who passed expressed frustration that they can’t have real confidence in themselves as students of this prestigious university since they may have squeaked in by taking the place of a more deserving female. The university has betrayed students of both genders.

Tired arguments resurrected

Part of what makes this a huge story is the financial, physical and mental cost involved in getting to the entrance exam in the first place.

Getting into medical school in Japan is tough in two ways. First, the level is simply very high, requiring one, two, three or even four years of devotion to study. Second, it is expensive. Private med school can cost you ¥20 million to 30 million ($180,000 to $270,000). A regular family of ordinary means cannot hope to pay for it.

Students going into private med school often are the children of doctors. Or at least they have the means. If they don’t, then public med school is the only choice. Even that can set your parents back a good ¥10 million.

And high school graduation cannot possibly prepare you in terms of the necessary knowledge for the entry test, so you’ll have to go to after-school prep school and study basically day and night. Of course, your family will have to cough up that tuition too. And that isn’t cheap either.

Some in the medical education world have known about and turned a blind eye to these universities who cheat women out of admission. Some say it has been an open secret.

“This is normal. All the schools are doing it,” said Dr. Ayako Nishikawa on the Aug. 5 edition of “Sunday Japon” on TBS. “If they just admit the best, the freshman class would be all female. Because girls are better. But then everybody will be ophthalmologists and dermatologists. Women can’t handle heavy people with hip dislocations.

“Few (women) become surgeons. After all, we need boys who will become surgeons. You can’t operate with a big belly. So at the end of the day, you’ve got to do something about gender ratios.”

Admittedly, she did at least recognize the need for such a gender adjustment to be announced.

While some criticized Nishikawa for promoting sexism, others echoed her and said she is simply relating the reality she sees as a physician. She is a plastic surgeon who has appeared numerous times on TV as a “celebrity doctor beauty.” Although her perspective might be different from ordinary physicians, there is no denying she is certified.

Or should that be certifiable?

Think of what she is saying. She looks at the world of medical study and says that affirmative action for men is fine and dandy. Then she justifies this position by enumerating women’s supposed physiological characteristics: They are weaker and have less stamina than men, will leave the profession once pregnant and so on. She related the lack of doctors in emergency rooms, surgery and other fields and claims that equal treatment will damage Japan’s medical system.

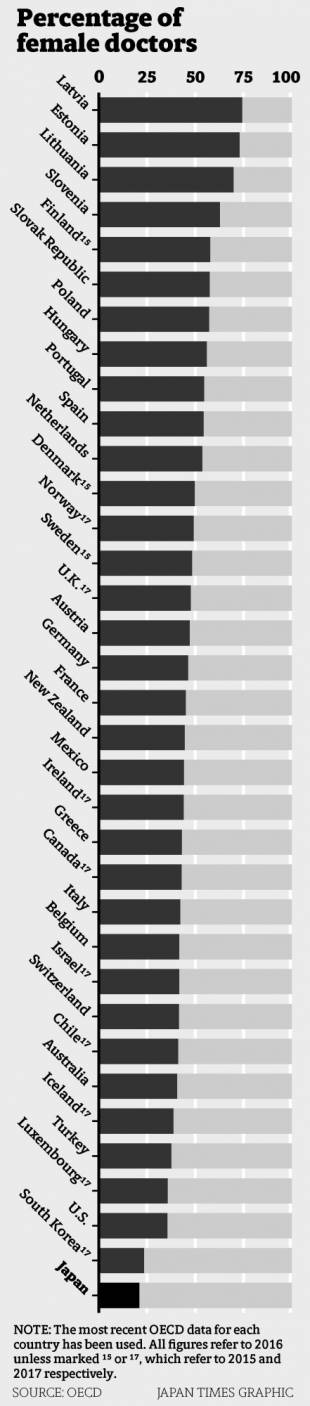

But do data from other countries back up Dr. Nishikawa’s assertions? Japan had the lowest proportion of female doctors of any Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development country (see graph), below the U.S. and South Korea. At the other end of the rankings, Latvia and Estonia lead the pack with more than 70 percent of doctors being women.

So her claims don’t hold up under universal scrutiny. Other countries seem to be doing fine with very high percentages of women physicians.

To the extent that she is right about Japan, it reflects more the miserable working conditions Japanese doctors are subject to. Men who have stamina and care nothing about work-life balance are the only ones perhaps that can manage the job.

Instead of trying to remedy that problem, Tokyo Medical University manipulated test scores to rob spots from women who had burned with passion to become doctors, studied their cardiopulmonary systems out and passed some of the most challenging tests in Japan. Imagine going through all that only to be cheated at the end of it.

A legal battle already won

It’s difficult to look at this from a labor law point of view. I first must remind myself what century we are living in.

Once upon a time, statistics were used to justify unequal treatment. This was called statistical discrimination. What it meant was that since women were more likely, from a statistical point of view, to work fewer years, get pregnant/give birth (much more likely), raise children and quit their jobs, therefore corporations were justified in 1) not spending the nonrecoupable resources on training them, 2) in not hiring so many women and 3) in treating men and women differently.

Before 1985, many corporations used this statistical discrimination to justify introducing internal systems that forced women to resign upon marriage and systems of retirement that differed according to gender.

In one case ruled on in 1969, Tokyu Kikan Industry defended its system of retirement that pushed men out at 55 and women out at 30 thusly: “Continuing each year to raise, across the board, the wages of female employees hired to do auxiliary work that doesn’t require special skills or experience just like the wages of (male) workers who do the main work and work that requires skill and experience makes no sense. It would not only lower employee motivation; it would interfere with efforts to streamline management. So, setting the female employee retirement age at 30 makes sense.”

But 1985 saw the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law (Kinto Ho), which prohibited discrimination from the recruiting stage, through hiring and to retirement. A gender-based retirement system was clearly outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1981 after a plaintiff sued Nissan Motor. Even today, however, employers find loopholes to treat female workers unfairly. But at least there is a clear legal framework that makes justifying gender discrimination impossible.

Tokyo Medical University discriminated against students who will be future workers. Many people, I think, have the impression that the highly specialized, “certificate-only” world of doctors and lawyers is more naturally gender-equal than the domain where ordinary private corporations dwell. My friend even became a lawyer because she thought she’d be shielded from the harsh sexist corporate world. I was shocked by this test score scandal and even more by the ho-hum reaction to it from many commentators.

We should really take a long, hard look at how unfair this score fraud is to female students, just as the corporate quit-upon-marriage and gender-based retirement age systems of yore were. Most importantly of all, the women who were bumped to make way for the boys need to be given immediate and proper redress.