BY CRAIG CURRIE-ROBSON

Jan 22nd, 2014

Every year, thousands of young native English-speakers fly to Asia in search of an adventure, financed by working as English teachers. They come from Australia, New Zealand, the U.S., Britain, Canada and elsewhere.

But it can be risky leaping into another country on the promise of an “easy” job. In Japan’s competitive English teaching market, foreign language instructors are treading water. “Subcontractor” teachers at corporate giant Gaba fight in the courts to be recognized as employees. Berlitz instructors become embroiled in a four-year industrial dispute, complete with strikes and legal action. Known locally as eikaiwa, “conversation schools” across the country have slashed benefits and reduced wages, forcing teachers to work longer hours, split-shifts and multiple jobs just to make ends meet.

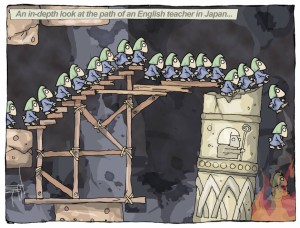

Armed with slick websites and flashy recruiting videos, big chains such as Aeon, Gaba and ECC send recruiters to Australasia, North America and Britain to attract fresh graduates. New hires come expecting to spend their weekends and vacations enjoying temples, shrines and exotic locales. Newcomers may also be lured by the prospect of utilizing that ESL (English as a second language) diploma or CELTA (Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) they’ve worked hard for. Yet from the start, they’ll effectively be customer-service staff, delivering a standardized product. Recruiting campaigns take full advantage of the prospective teacher’s altruistic angels. They look for suckers.

Once the work starts, eikaiwa keeps teachers busy and close to broke. At considerably less than the average Japanese salary, big English schools pay new teachers just enough to get by in Japan and not much more. The videos do not mention that they’ll have barely 10 days off per year, and find themselves trudging into the language center on public holidays and at Christmas. Nor do eikaiwa schools warn that the cost of living and the expense of domestic travel in Japan will stretch a new teacher’s salary. Many can barely afford a trip home once a year, time permitting. If a teacher stays for a year or two, as most do, they can afford a ticket home and again, not much more. When industry leader Nova collapsed in 2007, thousands of broke foreign teachers were stranded in Japan. Qantas offered cut-price flights home for Australian nationals.

Moreover, teachers can be locked into apartment contracts that make leaving the company difficult or expensive. The work schedule keeps teachers too busy to get many private students and many contracts insist on exclusivity, making it problematic to get outside work through private teacher matchmaking agencies such as Atlas. While Japanese law allows teachers to work elsewhere, it is also perfectly legal for schools to draft contracts that forbid it, making it easy for them to fire teachers for breaking the rules, or at least pressure them into toeing the line.

Working in the “Big Eikaiwa” chains often limits a teacher’s career scope. In a traditional Japanese company, skills are not necessarily transferable, because Japanese firms view company loyalty in an almost feudal sense. A former Toyota manager is rarely welcome at Mitsubishi because whatever corporate conditioning he’s had, regardless of the similarities, is considered tainted by the competition’s way of doing things. The same applies to an experienced teacher moving to a competitor. It is possible, but major chains each have their own methodology. A teacher might as well be a divorcee, trying to land a date while they’re considered “damaged goods.”

In any case, moving from one big chain to another is usually just a step sideways, as pay and conditions do not vary greatly; moving to a smaller school often means lower pay or a part-time assignment. Perhaps the main benefit is that the international experience will look good on teachers’ resumes when they return to their home countries.

Experience in Big Eikaiwa also limits development when teachers do move out of the corporate environment. Often a teacher indoctrinated in corporate methodology finds it hard to adjust to a more parochial environment.

Says James, a head instructor at a regional school in Sapporo: “I’ve had good teachers, experienced teachers, come from the big schools. The first time they pick up a real textbook they don’t know where to begin because all they’ve ever known is their school’s routine. They need to be retrained, in a way. One guy asked me if it was OK to sit down during a lesson because his previous school had never allowed it. I understood then why they take pay cuts just to feel human again.”

For those looking to stay in Japan for the longer term, the glass ceiling is alive and well. Few foreigners climb to anything above middle management, and CEOs are rare. The most a foreign teacher can normally aspire to is head instructor at a branch or a cluster of branches. Their brief is usually limited to overseeing other foreigners.

Most branch managers are Japanese and have ultimate authority over head teachers. Subjective student evaluations, based on woolly customer-service goals rather than learning results, determine a teacher’s raises, bonuses and promotion prospects, if there are any at all: the Berlitz union action started after the parent company posted record profits while teachers’ pay had been frozen for 16 years. At Gaba, targets for advancement such as total lessons taught or the number of positive evaluations are often revised upward to make them harder to attain.

Japanese tend to view foreigners as temporary, transient workers, and that perception becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The big schools know they have an advantage because there has always been a steady stream of foreigners looking to fund their Japanese adventure. They know the teachers lack the resources to challenge them — the language skills, the legal and local knowledge, the contacts, and even the time on their visa, which is often tied to their employment at the school. More cynically, they know that the teacher married in Japan with a young family is unlikely to vote with his or her feet. They certainly don’t pay the teachers enough to afford a lawyer. They’d be crazy to.

Indeed, there is little advocacy for foreign workers in Japan. With foreigners making up such a minority — less than 2 percent of the population — and with an aging society, declining birthrate and associated economic difficulties on the horizon, the plight of a relative handful of foreign teachers is hardly a societal priority. Moreover the fees students often pay, along with memories of the bubble years, lead them to the erroneous conclusion that English teachers make good enough money as it is. They’re often shocked to learn eikaiwa instructors get such a small cut for their efforts — at Berlitz or Gaba, for example, about a quarter of the per-lesson fee. There is no broad awareness of the discrepancy between lesson fees and instructors’ salaries.

The law does help, as the courts are not wholly unsympathetic toward workers. However litigation is costly and time-consuming and again, foreign teachers are uniquely disadvantaged in both respects. In Japan there is the saying that “The nail that sticks up gets hammered in,” adding an element of shame to standing up for yourself. This hampers the prospects for industrial action in general in Japan, and for a society where uniformity and complacence are considered virtues, the idea that foreign workers should be entitled to “special” privileges is perhaps asking too much.

This leaves collective bargaining the only viable option. At schools such as ECC, where the company has embraced the unions and listened to their requests, this has been a ticket to better conditions and greater job security, not to mention productivity. At Gaba and Berlitz, where management has dug in its heels and faced industrial action over nonrenewal of union members’ contracts, it has led to greater tensions and ongoing court battles.

In the small schools where teachers have been unable to fight back by weight of numbers, their benefits and rights have been largely at the whim of the employer. Some are benevolent, others shady. Most fall somewhere in between, as struggling schools do the best they can and are always looking to cut costs. But in the big schools where large unions have been possible, collective bargaining and court rulings have helped keep the most egregious exploiters in line. It pays to unionize.

Amid profits and expansion, what makes Big Eikaiwa keep slamming teachers — and teaching standards — down year after year? Why are the star players in the game on the lowest rung?

The answer is surprisingly simple: Because the teachers put up with it, and because the schools have figured this out. As long as there are people willing to take a leap and see what Japan holds for them, there will be employers willing to exploit that desire.

Teachers who have greater career aspirations or who simply can’t take it anymore go home. Some are sent home in disgrace or disgust. The rest are survivors who manage to settle in. Whether it be down to love, family, cultural or travel interests, they simply suck it up and soldier on.

Craig Currie-Robson works at a local language center in Sapporo. During his years in Japan, he has also worked for large eikaiwa chains as well as international kindergartens and on assignments for corporate clients and tertiary institutions.

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2014/01/22/general/teachers-tread-water-in-eikaiwa-limbo/#.UuNEOXmu6uW