The Tokyo District Court handed down its verdict in the Fujibi case last February, with the Tokyo High Court upholding it in July. On both occasions, I couldn’t believe my ears. The courts ruled that labor union Zenrokyo Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo Rodo Kumiai (Tokyo Roso) had committed defamation and damaged the creditworthiness of Fujibi, a medium-size artwork printing company.

Articles 1.2 and 8 of Trade Union Law explicitly exempt labor unions from civil and criminal liability when conducting legitimate labor union activities. This has been broadly interpreted thus far to give unions extraordinary leeway to dish out harsh criticism of their employers, whereas normally such public criticism would constitute illegal (possibly criminal) defamation (meiyo kison) or obstruction of business (gyōmu bōgai). Consumer boycotts are illegal (possibly criminal), whereas strikes by workers are protected by the Constitution, even if they hurt the business.

So these courts ruled that Tokyo Roso’s actions were not legitimate union activities. What were the actions and what led to these verdicts?

The precursor to Fujibi (aka Fuji Fine Art Printing Co., Ltd.) was established in 1918. Until recently, nearly all of its operations were “insourced” to its subsidiary Fuji Seihan, which made proofs (seihan) for printing. The companies shared the same premises. The president, chairman of Fujibi and the CEO of Fuji Seihan were all part of the Tanaka family, making for a typical family-run business.

Fujibi sued two regular workers and one part-time worker at Fuji Seihan. Although all 14 employees of Fuji Seihan were in the local chapter of Tokyo Roso, the three defendants make up the executive of the local. Unusually, no executives of the parent union (Tokyo Roso) were sued.

Moreover, the three were sued as individuals despite their actions having been conducted as part of the union. Usually, unions are sued rather than individuals, although it’s worth remembering that Berlitz Japan sued not only the parent union and the local chapter but also executives from both in their 2009 case against striking workers. In Fujibi’s case, the parent company and not the subsidiary sued the local union and not the parent union.

So why did Fujibi choose to sue them as individuals? I can think of a couple of possible reasons. One is that the company thought that targeting them as individuals might intimidate them more, isolate them from the parent union and break down their will to fight. Another is that the company might hate unions so much that they couldn’t bring themselves to recognize the unions’ existence even by suing them. Either way, let’s look at what happened.

Fuji Seihan filed for bankruptcy with the Tokyo District Court in 2012, and in September of that year the court granted it protection from its creditors. With the bankruptcy in hand, the subsidiary fired all 14 employees on the spot, without notice, says the union.

The employees had heard that earnings were hurting, but they never imagined things were that dire. The union immediately demanded collective bargaining with Fujibi, insisting that the parent take responsibility for employing those who had worked at the subsidiary. Fujibi agreed to discuss things twice, but each time they insisted they had no obligation to engage in collective bargaining since they were not the employer. The union says Fuji Seihan also unilaterally moved the union locker as well as its bulletin board, and told all union members that they were prohibited from entering the company premises.

The labor union took offense at these anti-worker actions and protested day after day in front of the company, holding banners and flyers with the following slogans: “Fujibi, hire the Fuji Seihan employees”; “Fuji Seihan’s bankruptcy is fraudulent”; “Fujibi group and the Tanaka family’s union-busting is unacceptable”; “Millionaire president, give us back our wages and severance”; “We won’t roll over while you treat us as disposable cheap labor.” Fujibi responded by suing the three local chapter executives for ¥22 million in damages for trespassing, defamation, damage to credit (shinyō kison) and obstruction of business.

As commonly understood, the above slogans are ordinary labor union slogans. If they constitute defamation or damage to credit, then many labor unions around the country are going to have their hands tied.

On Feb. 10, the Tokyo District Court ordered the three defendants to pay a total of ¥3.5 million between them for defamation and damage to credit. The three appealed to the Tokyo High Court, which upheld the same ruling on July 4.

Labor lawyers around the country have expressed alarm at the “crisis” threatening ordinary labor unions in the wake of these rulings. Lawyers came together to form a powerful team to take the ruling to the Supreme Court in a hail-Mary hope that they can somehow get the top judges in the land to see reason (an endeavour that’s unlikely to succeed).

We’ll have to wait and see. Please keep your eye on this case. In most situations, the Supreme Court simply refuses to hear cases, but fingers crossed.

Freedom of expression is a crucial tool that labor unions need to take full advantage of if they are to have any chance of realizing their demands. Japan recognizes that the law must strongly favor workers when it comes to industrial relations. The exemption from liability for legitimate trade union activities does not apply to employers. The thinking is that there is an overwhelming imbalance of power between workers and employers, and efforts to reduce this imbalance must be made. In a way, this resembles a form of affirmative action for workers.

In the famous case involving Prima Ham, the company president told striking workers that “we have no choice but to make a very serious decision.” The Supreme Court ruled in 1982 that his comment was an unfair labor practice (i.e., anti-union practice), in that it threatened the union and could have led to a chilling effect on union activities.

AIG Star Life Insurance sued a labor union over leaflets that used “unfair dismissal,” “Employees are disposable,” “unilateral dismissal,” and other similar expressions. The Tokyo District Court ruled in 2005 that although (deep breath) “the comments did defame the company in part, they were made as part of union activities, and considering in a comprehensive manner all the conditions at the time, including the objective, the manner and impact of the expressions, the only conclusion to be drawn was that they were of a nature that is acceptable as legitimate union actions according to social norms, and thus any illegality was thereby negated.” Long story short, the union won.

Employers must be quite unhappy about this legal favoritism toward workers and unions. But without it, workers remain stuck in an extremely weak and vulnerable position, making it impossible for them to stand up to the often-arbitrary behavior of management.

In labor law academia, this refers to the jūzoku rōdōron (submissive worker theory), according to which the law must protect labor union activities — the alternative being that workers will perennially be forced into submission by their employers. I can only say that the recent high court ruling against the Fuji Seihan employees suggests that the judge does not fully appreciate the special nature of and role played by labor unions.

It is important to understand that these verdicts were based not so much on the language on the demonstration banners but rather the fact that the slogans called out the parent company and its president by name, even though the parent company was not the legal employer of the union members. For example, a slogan that named the president of the subsidiary (the actual employer) and said something to the effect of “You fugitive f—-er, fattening yourself up while robbing the workers of their wages and severance pay” was deemed legitimate by the court. In a sense, the union lost on a technicality, not due to the harshness of the message. The point of contention in this case perhaps was not freedom of expression but rather the legality of targeting a company with no employment relationship to the defendants.

While Fujibi declined to comment for this article, citing the fact that the union members are appealing to the Supreme Court, I did speak with one of the three defendants. Her name is Junko Nakahara, general secretary of the Fujibi Group local branch of Tokyo Roso. She explained how they had worked hard in collective bargaining over two decades.

When she was served notice of the case against her, Nakahara, 64, said she was “shocked that I was being sued as an individual, not as a union.”

“I had worked there more than 20 years. Fujibi and Fuji Seihan occupied the same premises, the same building, the same business. They were inseparable. So I cannot accept Fujibi’s claim that it is a separate and unrelated company.”

Nakahara notes that local residents encouraged them when they were demonstrating every day outside the company, urging them not to give up. “I am so thankful to them,” she said.

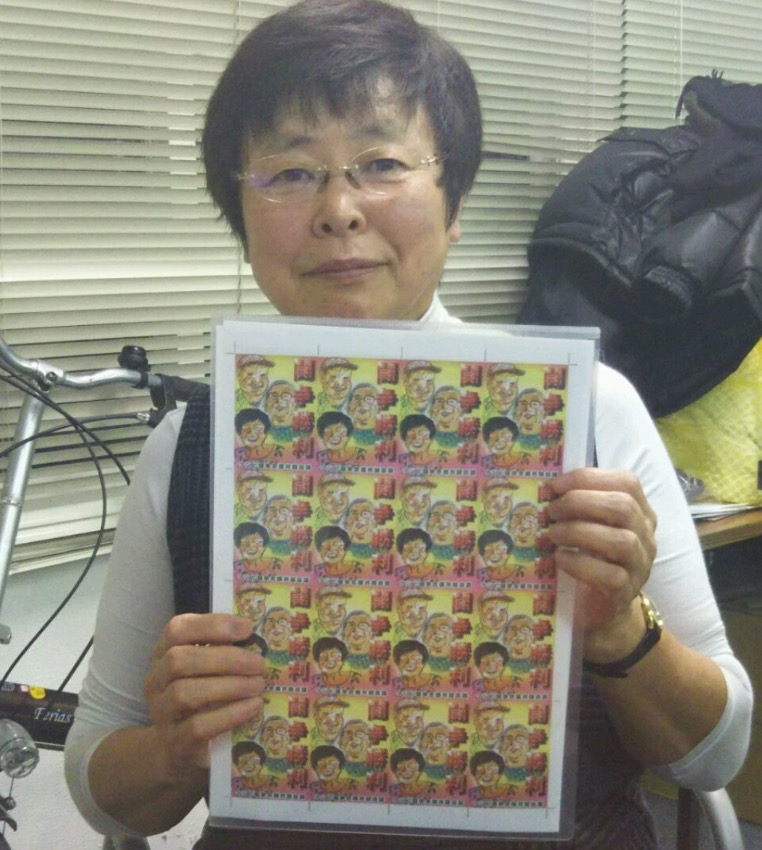

“There are so few ways for fired workers to raise their voices, but we had no choice but to raise them high with all our might,” Nakahara explained. She also told me that 1,151 different organizations lent their support to the three defendants, including by signing petitions. “This warmed my heart and gave us real courage. One member drew our faces in a show of support.”

I asked Nakahara whether the ground campaign was still being fought.

“Yes, once a week we are out there leafletting,” she said. “The Labour Lawyers Association of Japan has also supported us. Some people tell us, ‘This is not a time to turn to activism,’ but I have no regrets. The sadness and anger of workers when they lose their jobs must be given a voice. We must continue to fight to protect our rights. Fortunately, we have many supporters, so I will continue to fight with all my heart and soul.”

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union. She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. Labor Pains appears in print on the fourth Monday Community Page of the month. Originally published in The Japan Times.