Matahara: turning the clock back on women’s rights

‘Maternity harassment‘ concept coined amid reports of bullying over pregnancy at work

BY HIFUMI OKUNUKI

“When I told my company I was pregnant, they fired me.”

“I was delighted to be hired by a company I loved. Then my boss made me promise not to get pregnant for a while.”

In last October’s Labor Pains, I discussed maternal job rights in “Labor law protects expectant and new mothers — to a point.” Today, I would like to address a new legal concept known as “maternity harassment,” or matahara, in the syllabic acronym engendered by this growing — and disturbing — trend.

So what’s behind the sudden increase in reports of matahara? And why now? I just don’t get it.

For one thing, both statutory and case law are crystal clear on the illegality of firings due to pregnancy. The Labor Standards Law stipulates that an employer cannot fire a woman in the first 30 days upon her return from maternity leave. If a company is considering letting a woman go even during the next 11 months, the burden lies with the employer to prove that the dismissal is not maternity-related. The Equal Employment Opportunity Law (kintōhō) of 1985 prohibits any kind of discrimination based on pregnancy, childbirth, taking maternity leave or other health issues.

The law is one thing; practice is quite another. Employers rarely welcome pregnancy among their employees, because it can interfere with the smooth operation of their business. The unfortunate reality is that many bosses wage low-level harassment against new and expecting mothers, dropping repeated snarky comments to make them feel less than welcome, following the letter rather than spirit of the law.

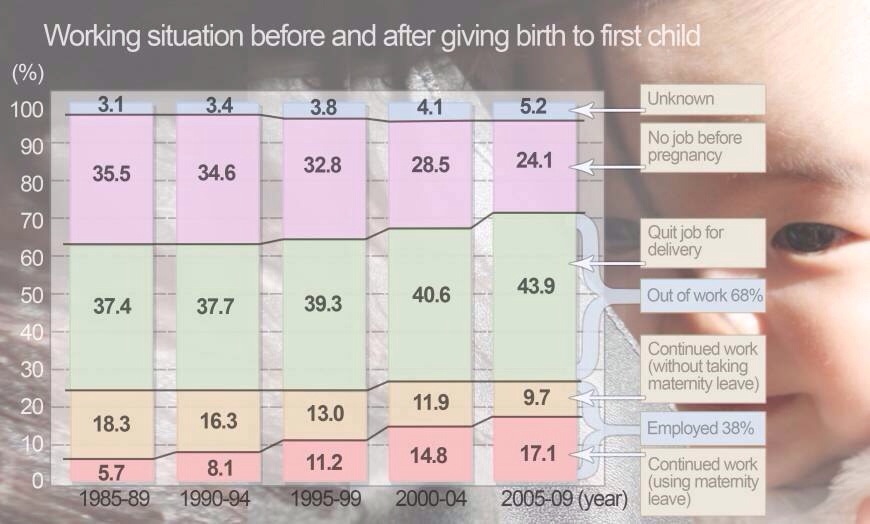

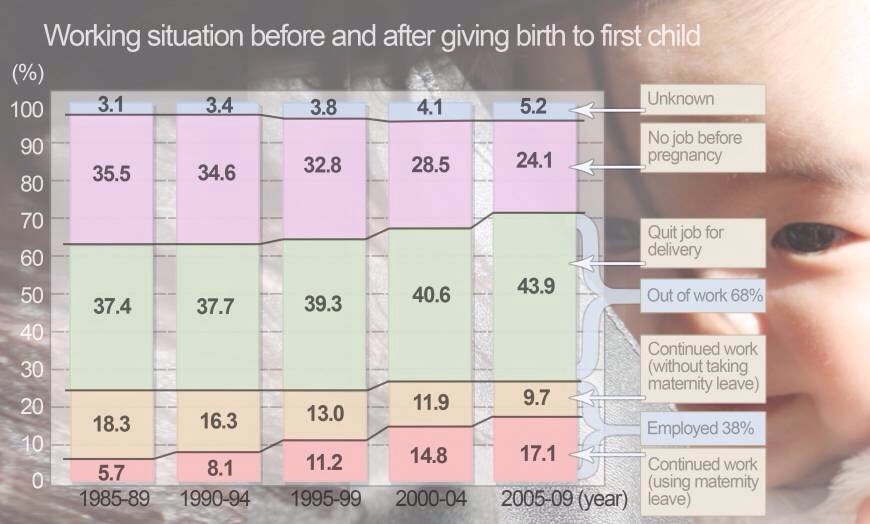

Employed women quit their jobs 62 percent of the time after childbirth, and the percentage is climbing, according to a 2011 study by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (see chart).

A famous precedent involving a refusal to renew the contracts of pregnant women is the Shokokai Uwajima Hospital case. The two plaintiffs were “semi-regular” nurses and caregivers at this hospital in Ehime Prefecture. They both worked on one-year contracts, had been renewed twice, and were refused renewal the third time, just around the time they became pregnant. They sued the corporation (Shokokai) that ran the hospital for reinstatement and lost wages.

The Uwajima branch of Matsuyama District Court ruled on Dec. 18, 2001, that not only was their nonrenewal “analogous” to dismissal — meaning it required a good reason, just as a dismissal would — but that the reason for the nonrenewal was in fact their pregnancies. This violated Article 8.2 (now Article 9) of the kintōhō and was an abuse of the right to refuse renewal, the court said.

The law clearly does not permit discrimination against women for getting pregnant or giving birth. Yet 12 years later, working women face formidable hurdles if they want children and also hope to hold onto their jobs. Many women feel guilty that their maternity will cause inconvenience to their company, superiors and coworkers.

Let’s look at public opinion, or at least one tiny corner of it. With nude photos of women and risque content, Shukan Gendai is what I would call an ossan (dirty old man’s) weekly magazine. In its Aug. 31 edition, popular 81-year-old writer Ayako Sono penned a piece called “To Spoiled Little Working Girls Who Always Blame Their Companies: If You Have a Child, Quit!” Note that even in the title, she calls women “little working girls” rather than “working women.”

To quote:

“If a woman gives birth, she should quit her job, then after years of raising the child, find a way to return to work. … Why do women insist on staying in their jobs even when it causes inconvenience to their companies? They probably worry that they won’t be able to make ends meet with only one parent working.

“I am of a different opinion. In my day we had to raise kids in dire poverty. Day-care centers now have waiting lists; it’s ridiculous. Children should be raised in the home. People used to live with their parents; grandparents could look after grandchildren, enabling the children’s mother to go shopping. I raised children while working.”

Sono apparently believes it was OK for her to continue working after having a child.

If a working mother today, scrambling desperately to hold down a job and raise a family simultaneously, were to read Sono’s article, she might laugh out loud rather than fume over this broadside, considering how detached from reality the writer appears to be. She might also note that Sono has lived a life of privilege, untroubled by such worldly concerns as day-care centers and job dismissals. She received support from her own parents, was able to do work she loved, and even gained some degree of prestige. Sono tells mothers to “find a way to return to work” yet offers no practical suggestions on just how to do that.

It would be tempting to dismiss this article as the ramblings of a cranky old woman looking back with nostalgia at the good old days while bemoaning modern society and young women today. But Sono is a best-selling author, former director of the Nippon Foundation charity and a member of Prime Minster Shinzo Abe’s Education Rebuilding Implementation Council.

It depresses me to see a woman in such a position of power tearing into our equality laws, calling working women spoiled and playing to the crowd in a magazine clearly read mostly by middle-aged men. The Shinzo Abe government has stressed the importance of self-help (jijo) as a new model for social security, as opposed to public help (kōjo). According to this model, we should not depend on society for help — this is a stance similar to Sono’s.

If Japan returns to this type of thinking, what will become of the country in 50 or 100 years? Many officials in the government today are blind to this danger, steeped in nostalgia and want to turn back the clock.

Depressing indeed.

————————

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as the executive president of Tozen Union (Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union). She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. On the third Tuesday of the month, Hifumi looks at cases in Japan’s legal history to illustrate important principles in labor law.

Originally published by Japan Times at:

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2013/09/23/issues/matahara-turning-the-clock-back-on-womens-rights/#.UlZpYBYijHg